The attraction. How do you drive it? How do you shift the gears? As a child, it was a mystery to me. How do you keep it from tipping over as you climb on? As a little runt, always the smallest in my class, I was impressed with the strength it took just to hold up motorcycle, especially a big Harley-Davidson. My dad was a daredevil and rode motorcycles, and once worked as a motorcycle courier. My mother was said to have ridden in his motorcycle sidecar on one of their dates. Always looking for role models after my father’s death, I was eager to try anything my dad used to do (see story on “My Father”). Motorcycles had the reputation for being dangerous. All the more interesting to me.

“The Wild One”, Stanley Kramer, 1953.

Then there was Marlon Brando. Most of us cadets at the Shattuck military academy in Faribault, Minnesota, idolized one of our more famous alumni. The rebellious Marlon had trouble obeying the rules of military discipline, and got the boot for too many demerits in his junior year, 1941. He had experience acting in school plays, and headed straight for New York City.

After making a big splash on Broadway culminating in Tennesee Williams’ “Streetcar Named Desire,” Brando’s film career blossomed. I entered Shattuck School in the Fall of 1952. In 1953, “The Wild One,” based on a true story, appeared, in which tough guys Brando and Lee Marvin and a gang of 40 black leather-jacketed motorcycle hoodlums terrorized a small town in California. We were captivated by the Brando image — the macho, misunderstood rebel. Before “Easy Rider” this film contributed greatly to the motorcycle mystique. In my fantasies I was ready to ride off into the sunset with Brando and 40 other bad dudes just having lots of fun and raising Hell.

Spring, 1959. My first motorcycling adventure. When the snow finally melts in a small College town like Northfield, Minnesota, a young man’s fancy turns to anything but courses, chemistry labs and books. Especially as a senior, it’s O.K. to be cynical, jaded, and ready to break down the prison walls. I had discovered the pleasures of California Rhine Wine by Paul Masson. Today its sweetness would put me off, but then it seemed to turn a spring afternoon in the sodden cornfields of Minnesota into a silk-screened reverie from Provence, sung by nightingales, and dappled with sunflowers.

Along came Peggy Hagberg, from Deerfield, Illinois, on whom I had a big crush. With a face resembling the film star Anita Ekberg, Peggy was tall, with a zany sense of the ridiculous, including me, and game for just about anything. The dormitories were segregated by the sexes, and women had to be in by 10:15 weeknights with no liquor on their breath. Yes, Carleton had breath checks, but only for women.

Students were not allowed to have cars at Carleton. Peggy and I decided to get a bottle of wine, rent a motorcycle, and go riding in the countryside. Somehow I found an Ole (student from our cross town rival St. Olaf College) who was nice enough to rent me his BMW for an afternoon. It was a fine, big, old German bike with a drive shaft instead of a chain. Since I had never driven a motorcycle before, the Ole gave me lessons. He also explained something about the choke lever for enriching the fuel mixture when you start up.

Peggy and I enjoyed the most wonderful feeling of liberation as we took off on the small roads that criss-crossed the farmlands of Southern Minnesota. Fortified by the Paul Masson, we felt like “Yippee, Free at last!” After a few miles, we started going slower and slower. The exhaust was getting smoky, and before long the bike came grinding to a halt. After trying to kick start the BMW ad nauseum, we realized it was kaput and pushed it all the way back to town. I had probably fouled the spark plug by leaving the choke on permanently. Still, the adventure was great fun and Peggy thought it was hilarious. We joked about it many times as we dated occasionally during the next 6 months or so, and I was proud to have taken the first step in motorcycling.

Steven and Anne-Marie, 1959

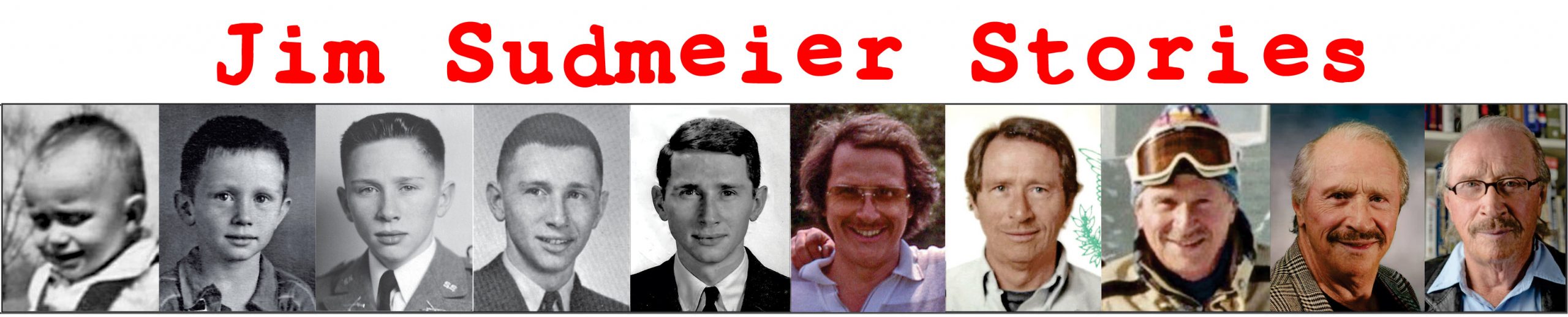

Spring, 1960. My first motorcycle. After propelling myself by bicycle for most of the school year around the campus of Princeton University in New Jersey, where I was attending graduate school, I decided it was time to get some serious wheels. Cars were allowed at Princeton, but I couldn’t afford one, and to buy one would have been “selling out” according to my value system. No Princetonians rode motorcycles, with one exception. Steven Rockefeller, two years older than me, son of Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, graduated from Princeton in 1958, where he was President of the prestigious Ivy Club (like fraternities but non-residential — only for meals and parties). In 1959 he married an au pair girl from Norway, blonde beauty, Anne-Marie Rasmussen. There were photos in Life Magazine showing him whisking her away on a motorcycle. Heck, I figured, if it’s good enough for Steven, it’s good enough for me.

I went to a motorcycle dealer on Route 1 outside Princeton and picked up a used Harley-Davidson 165, about 1957 vintage, at a cost of about $250. The 165, sometimes called a ‘Hummer” was copied from the German DKW RT125 right after WWII as part of war reparations. The two-stroke engine had 165 cc displacement, generating 5.5 hp. It had a 3 speed transmission, shifting on a left foot pedal. Hear it idle.

A curious hybrid: “Hell’s Ivy Leaguer” outside Frick Chemistry Lab.

The dealer also showed me a curious thing. It was an ultra-sleek, clean little Honda motorcycle from Japan. I could have had the new Honda for the same price as the used Harley. It even had an electric starting motor. Hell, I thought, Japanese junk. If it’s too good to be true, then it must not be true. This was the leading edge of the Japanese takeover of motorcycles, but I could not imagine it, so I passed on a terrific deal.

Soon I needed to get home to Minnesota, where I had a summer job doing research for the 3M company in St. Paul. This was going to be a grueling 1250 miles on a motorcycle whose top speed was 45 miles per hour. I packed my saddle bags for a three day trip. In case of rain I brought my khaki U.S. Army surplus rubberized nylon poncho doubling as a tent (and canoe sail). I wore motorcycle boots and a helmet. I would use local two-lane highways, partly to save the money of tollways, but also to avoid being steamrollered at my ridiculously slow speed.

Princeton, New Jersey to Minneapolis, Minnesota in 3 days-1250 miles.

Well, thank God for the poncho, because it started raining on my first day, May 30, and continued for two days. At times it rained so hard I had to stop and empty the water out of my motorcycle boots. Crossing the Allegheny Mountains of Pennsylvania on local roads with few tunnels was a major hassle. Almost no towns were bypassed, and having to stop for traffic lights in almost every town was incredibly time consuming. These days would involve 12-hours of riding punctuated by truck-stop restaurants and cheap motels.

My trusty but slow Harley-Davidson 165.

I learned a trick for going faster. Get right behind those big 18 wheel trucks. Not only did it provide streamlining, but at a certain point the vortexing air currents could even pull you along at 55 mph or more. The obvious problem would arise if the truck had to stop quickly, but that never happened.

On the third day the weather was clear. Driving through Wisconsin was actually a pleasure in the warm, early summer air. Then they hit me. THWAPP. Right in the face despite the windscreen, and it hurt. THWAPP. Another one in the face. THWAPP. This went on for hours. Now I knew for certain that the date was June 1. Yes, the June Bugs, as I’ve noticed on other occasions, are very punctual. They stay in their hiding places through the evening of May 31, and then precisely on June 1 they appear. Measuring almost an inch long, fat, brown, and aggressive flyers, they must weigh several ounces apiece. They fly as if drunk into windows, screendoors, and other solid objects including motorcycles.

Anyway, I had reliable transportation that summer from my home in Minneapolis to the 3M laboratory in St. Paul some 10 miles away each day. I had a good job doing organic chemistry synthesis in the Thermofax division. The job paid well, and with a little extra money in my pocket, I was ready to move up to a more powerful motorcycle for the ride back to New Jersey.

Megaphone. Wish you could hear me

Fall, 1960. My second motorcycle. Shopping thru want-ads, I found a used Triumph Tiger Cub for sale, costing about $400. The English-made Triumph was known to be a very hot bike (Brando rode his own Triumph Thunderbird in the movie, while Lee Marvin owned a Tiger Cub but drove a Harley in the film). My particular Tiger Cub had been used for racing. It had a racing cam, and a megaphone instead of a muffler.

Triumph Tiger Cub like my ~1958 vintage.

The 200 cc four-stroke engine burned gasoline, not a gas/oil mixture, and probably generated more than the rated 10-14 horsepower due to the engine modifications. With a four-speed transmission, shifted with the right foot, this one should be able to cruise at 60 or 70 mph on the highway. The thing about this Tiger Cub, which sold me right away, was its roar — like a ruptured banshee. It was scandalous, and could be heard for blocks. (What an asshole I must have been!!)

One small problem was that I had bought the Tiger Cub only a few days before I had to leave for the East Coast. I knew it had been abused and had a few “idiosyncrasies”, such as the kick starter not working. I had to push the bike down the street, jump on, kick it into gear, and let out the clutch. There was no time to learn about the operation or care of the bike, and there was no manual. I transferred the saddle bags from the Harley to the Triumph. There was just enough room for my toiletries, a few clothes, and some rather expensive textbooks I had purchased for the Fall Quarter at Princeton Graduate School.

Al Burgoyne, my ex-roommate from Carleton (and future Best Man), would be driving his old Chevrolet sedan eastward from Green Bay, Wisconsin to Duke University Law School in Durham, North Carolina about a day after I was heading east to Princeton, NJ. Just in case I needed help, I called Al and told him I would be going straight east to Green Bay, Wisconsin instead of southeast toward Chicago, showing how little confidence I had in the Tiger Cub’s condition.

I crossed the St. Croix River into Wisconsin at Hudson, and I was making pretty good time. Another hour or so, and I got past Eau Claire. The megaphone was hot as blazes, as you would expect, but the engine was also starting to smell pretty hot. I stopped at a gas station and put in some oil. (I never had to put oil into the Harley, except mixed with gas, so this was a new problem.) There were several screw caps, but I had no clue which one was for the oil, or how much to put in. So I gave each one a generous allowance. Continuing on my merry way, the engine seemed to be running a bit cooler. Then I looked down and noticed that one of the straps holding the saddle bags had broken, and I stopped immediately. Uh-oh. The right-hand saddle bag was open and had flipped right over on the megaphone tailpipe, which had burned a perfect 1-1/2″ circular hole through the leather. The contents of the saddle bag were strewn along the road for probably a mile back.

I picked up everything off the ground I could find. My toothbrush, my toothpaste, a T-shirt with 8 perfect 1-1/2-inch holes burned in revealing how it had been folded. Everything else was long gone, including my brand new $40 Inorganic Chemistry text. I decided to drive back and look for more of my stuff. To start the engine, I ran the bike down the road, kicked it into gear, popped the clutch, and THE CHAIN BROKE…

Desolate, I walked to the nearest house and called, collect, to my most respected, dearest friend, Allen G. Burgoyne, Jr. “Al, come and get me, please.” The poor guy drove the extra 200 miles out of his way just to pick me up, and then another 500 miles or so to take me to New Jersey. We had to remove the back seat of his car and put this stinking, oily bucket of bolts into the rear.

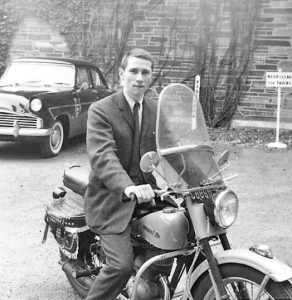

My room was on the 2nd floor, left side in this photo. Einstein used to live on 112 Mercer St, ~300 yards away until his death in 1955.

The Princeton Graduate College is a stately institution standing a little apart from the rest of the University, surrounded by a golf course. Truly Hogwartian, we had to wear black academic robes to our evening meals in the main Dining Hall, where grace was always said in Latin. After one of the porters showed me to my room, I searched the bowels of the old building for some place to store my greasy motorcycle wreck. Lo and behold, there were several empty storerooms in the old basement, and I appropriated one for the newest unenrolled, Princeton Tiger. Over the next 4 or 5 months, laboring over a set of shop manuals, I would breathe new life into the monster asleep in the dark, cold cellar.

What are chances that the Triumph used standard American or metric nuts and bolts? Uh-uh. It’s a completely different system known as “Whitworth.” So I had to purchase a new set of tools to work on the bike. (This was a small forewarning of the inconveniences I would face when living 3 months in 1973 in Oxford, England. The lights in my apartment suddenly go off. I fumble in total darkness for some tiny, obsolete sixpence coins, and crawl on my hands and knees into the kitchen to feed the electric meter in the cupboard under the sink. I go to the store for some milk. They’re sold out. I ask, “How can you be out of milk?” Carrying home a dozen eggs in a paper bag was also pretty quaint. I love the English people and their sense of humor very much (I am happily married to a lovely Englishwoman), I just found some of their practices back in those days a bit baffling.)

Dining Hall, the old Graduate College.

I stripped the engine and the entire bike, down to nuts and bolts. Then I cleaned, lubricated, replaced any worn parts, and put it back together. Late one evening in March, with the new kick starter I turned the engine over, there was a beautiful sound in the dungeon echo chamber, and the BEAST ROARED ONCE AGAIN. I rolled it out for a test drive in the fresh springtime air. The only problem was that my left leg was broken and encased in a long-leg plaster cast from a skiing accident during Christmas vacation in Stowe, Vermont (see “Tom and Rita” story).

I wasn’t sure whether to ride with the cast on top of the handlebars, more dangerous, or just hold it up off the ground, which took more effort. Anyway, the shift pedal being on the right foot, I was able to take the Tiger Cub for some kind of a test drive. Everything was 100% ship shape, and the Cub was so full of pep that it was hard to keep the front wheel from leaping off the ground.

In 1961, during the height of the Cold War it was rare to have a visiting exchange student from Russia. There was one living in the Grad College named Alexy, an aeronautical engineering student whom I befriended. I let him take the Tiger Cub on longer test drives around the campus. One day I visited his room and noticed that he kept his closet door locked. Jokingly, I asked, “What’s in there? The transmitter?,” with a smile. He definitely did not think it was funny.

When my research advisor left Princeton in the summer of 1961, I arranged to continue my thesis research with a new professor I’d met in Chapel Hill, NC. I was still in the long leg plaster cast in June (total 7 months), and I couldn’t see how I could bring the Tiger Cub to North Carolina, so I sold it to a buddy, Chris Cupas. A Bostonian of Greek origin, Chris had been a Harvard undergraduate. Later he became an Organic Chemistry professor at Case Western University, Ohio, and then went to medical school for his MD degree, and wisely opted for the life of an anesthesiologist.

During the summer of 1961, Chris was riding the Tiger Cub somewhere on Cape Cod late at night. The bike stopped running, and he thought it might be out of gas. So, in his wisdom (and probably a little drunk), he opened the gas cap and lit a match to take a look. KaBOOOM. Chris was not seriously hurt, but there, in a smoldering piece of metal and rubber lay my baby that I never got to ride properly. I had especially hoped to ride her off-road. I hope Chris gave her a decent burial.

Afterwards. In Chapel Hill, my wife and I rode an Italian Vespa motor scooter to work for a year or two before breaking down and buying a car. The last time I was on a motorcycle was about 1982 when, Jim Myers, an old friend and former neighbor from Santa Monica, California came out to visit in Riverside on his new full-size Honda 500. He let me take it out for a spin on El Cerrito Drive. Despite of the 22 year gap, it felt as if I’d been riding all my life. I rode for less than 5 minutes, going through all the gears, during which, from a glance at the speedometer, I was astonished to have reached 80 mph. It was still a kick.

Demonstration. Do you want to take a 2 minute ride on a Tiger Cub down an English country lane?

Jim Sudmeier

First draft

Revere, MA

February 2011