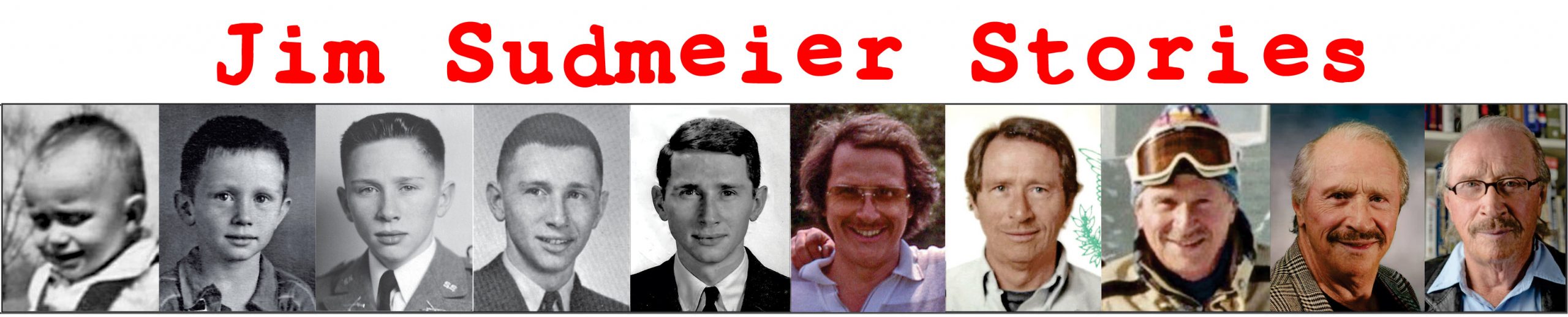

My father, Carl H. Sudmeier

Born: August 20, 1911 in Minneapolis, Minnesota

Died: October 24, 1942 in Lake Osakis, Minnesota

The Funeral

I got up as high on my tippy-toes as possible to look into the casket. It was Daddy, all right—pale, motionless, with his big hands crossed on his stomach. As a 4-1/2-year-old boy in 1942, I knew nothing of death. I was just able to reach his cold right hand. I lifted it up a few inches and it flopped back down. I was surprised at the stiffness of my 31-year-old daddy. It was all so weird—him wearing a suit and tie for the first time in my memory, lying on a bed of white satin. Daddy was surrounded by wreaths with silk banners and garlands of flowers that filled the Henry W. Anderson Mortuary with overpowering fragrances.

I didn’t know how to behave. Almost everybody else was crying. My 5-1/2-year old sister Marilyn couldn’t stop. But I felt no grief. Daddy was the one who spanked us with the belt, and teased us mercilessly with the “Dutch Rubs,”i.e., knuckles rubbed hard on the scalp. When we came to him lying on the sofa after work, he would trap our heads between his legs until we cried.

Daddy had a temper. He always had trouble with his 1935 Ford sedan. Sometimes it ran out of gas and sometimes it wouldn’t start. He would disappear under the hood of the car as he tried to start the engine. The car would go WAH–WAh—Wah—-wah—, and then Daddy would yell “SHIT!” If we didn’t finish all our food he would SMASH the kitchen table with his fist, making all the dishes jump. I dared to hope that maybe our lives would improve with him out of the way.

Carl’s History

Carl and his bounty of ducks

Carl Henry Sudmeier was born in 1911 in Minneapolis, Minnesota, an only child. He soon developed into a 6 foot 2 inch, strong, lanky outdoorsman, sportsman, and daredevil. Seemingly afraid of nothing, he was photographed as a youth hanging by one arm from a telephone line well away from the poles. At the zoo he would tease the bobcats into a frenzy. After his dad died when Carl was 14, he was spoiled by his mother. During the Great Depression he enjoyed wearing fine clothing and hats, and seemed to lack for nothing. He shot 16 mm home movies, which showed him with his friends smoking cigarettes, golfing, boating, fishing, skeet shooting, duck hunting, and ski jumping. He played popular tunes on the piano, and did pre-medical studies at the University of Minnesota, where he was nicknamed “Doc.”

In 1936 Carl met my mother, Ingrid, a simple but spunky girl raised on a poor Wisconsin farm, and everything changed. With his hazel eyes and dark, bushy hair, he was good looking, well-off, adventurous, and funny. She fell for him and the romantic letters he wrote. He was enamored by Ingrid’s charms and by what he perceived as the more peaceful life of her country folk.

After she got pregnant in 1936, they got married, and Carl’s plans for higher education were finished, leaving him resentful. Ingrid was soon frustrated with more motherhood than she was prepared for. Carl found work as a motorcycle courier for the Bureau of Engraving, and as a union mail carrier for the Minneapolis Post Office. Only outdoor work would be acceptable to Carl. By March 1942, there were three children, one girl and two boys. The family obligations presumably kept Carl out of WWII. But he could always sneak away on weekends for some outdoor sports.

Carl was always an expert hunter of ducks and pheasants. He had all the gear—guns, decoys, duck calls and a duck boat. In the basement of our house at 3020 Longfellow Avenue he had a gas stove with a giant pot of melted paraffin for stripping off the feathers. We got used to spitting out the occasional buckshot while eating game.

The Disaster

Everyone was aware of the instability of duck boats. Nevertheless, most of the movies of Carl in his duck boat show him standing up, using a long oar similar to today’s paddleboards. Was this the most efficient way to get around, or just the most macho?

Carl paddling duck boat (from 16mm movie)

On Saturday, Oct. 24, 1942, Carl and his fellow mail carrier, 49-year-old Oscar C. Crandall, got up early and drove the 125 miles northwest of Minneapolis to Lake Osakis, Minnesota. The weather earlier in the week had been very mild—in the 70s daytime and 40s at night. But a cold front had moved in by the 24th, and it was below freezing at night with a high of only 35, and even a trace of snow falling. Lake Osakis had a handful of resorts on the east and south sides of the lake. But Carl and Oscar launched their duck boat on the west side of the lake near Schelfhout Point because of the proximity to the quarter mile wide patch of reeds offshore—ideal habitat for ducks.

At approximately 9:30 AM a catastrophic mistake occurred. The duck boat capsized and both men ended up in the near-freezing water, yelling for help. Newspaper articles speculated that the men both fired their guns in the same direction at a flock of ducks, though there could have been other factors. Sometimes hunters have been known to warm up with a nip or two of spirits, though I never heard that my dad was a habitual drinker. Another duck hunter heard the yelling and drove to the farm of Pete Schelfhout, who called Okkie Johnson, who in turned called the Hanson brothers. Norman and “Rusty” Hanson were proprietors of the Idlewilde Resort at the south end of the lake in the village of Osakis. The Hanson brothers drove their motor boat about 1-1/2 miles straight north to the reedy area.

It took some time to find the accident scene. By that time Crandall was missing, with only Carl left hanging onto the overturned boat. The newspaper article reported that the men had been in the water for an estimated hour or more. The report said, “With considerable difficulty he [Carl] was pulled into their boat and was apparently out of his mind due to the exposure and suffering. He had to be forcibly subdued and shortly after this was accomplished he became unconscious and never recovered.”

In a Scientific American article published in January 2009, author Coco Ballantyne reports, “When you first go into extremely cold water there is this weird response called a cold shock response. People start to hyperventilate immediately. For one to three minutes you breathe very fast and deep, uncontrollably… Many of the symptoms of hypothermia resemble those of a drunken stupor: sleepiness, clumsiness, confusion and slurred speech.”

The newspaper report went on to say that the motor boat bearing Carl’s lifeless body docked at the Schelfhout farm, where medical personnel and an ambulance were waiting. Artificial respiration was begun. Later Carl was brought to the town of Osakis where artificial respiration was continued for several hours until 1:30 PM. The sheriff and the Hanson brothers went back to the accident scene early in the afternoon, and strangely “there saw the other man [Oscar Crandall] standing erect in seven feet of water.” He was brought to Osakis, where both men were taken to the local funeral home and examined by the Todd County coroner. Then they were shipped to separate funeral homes in Minneapolis. My sister and I still remember the phone call. It was presumably from the coroner, being answered by Carl’s mother, our “Grandma B,” who happened to be baby-sitting at our house. She screamed and wept uncontrollably like we had never seen her before or since. We were terrified, and unable to console her.

Some 10 years later at the Sportsman’s Show in the Minneapolis Auditorium, I met a couple men at the Lake Osakis booth who knew some details of my father’s death. They pointed out that the rescuers hit Carl in the head with an oar hard enough to fracture his skull, sending him into shock. One can’t fault Good Samaritans who also need to save themselves, but the causes of Carl’s death were actually fractured skull, shock, and exposure.

Missing Dad

As I grew older I began to understand what I had missed. I found that boys with fathers were better at sports, more able to defend themselves, more confident, and less likely to be bullied as I certainly was. I’ve never heard of an Eagle Scout without a devoted father. I was kicked out of the Boy Scouts for horseplay, with no backup. I had problems with my identity — knowing who I was without the mirroring of a father. How do men behave? What’s it like to be a father, or husband? We see it often in today’s society – boys without fathers are angry. I had a lot of anger and I craved attention. I lived in a house with two domineering women, my mother and my grandmother. My teachers in the Minneapolis public school system were also mostly strict, older females that I disdained.

I preferred being the Class Clown and chief spitball thrower. I was a bed wetter till about age 10 and picked incessantly on my younger brother of whom I was jealous. It was an endless cycle that kept me perennially in the doghouse. I was taught that that there was something wrong with me. Except for Shame and Guilt, my oldest companions, I was numb and alone.

I needed men as teachers and role models. When I found a good male teacher in the public school, I knocked myself out to please him, and got straight A’s. My life was saved by my enrollment at Shattuck School in Faribault, Minnesota, the all-male military school, (today Shattuck-St. Mary’s is coed) thanks to the financial aid of anonymous donors. All the teachers, called Masters, were male, and all were excellent teachers. The classrooms were small, usually containing 13 students or less. Every day was regimented, from Reveille, the bugle call at 7:00 am, to study hall at 7:30, to lights out at 10:30 pm and the playing of Taps.

Days were filled with shining shoes, making beds, cleaning rooms, academic studies, military drilling, athletics, and I thought it was great—even the hazing and shagging by the old boys. We were rewarded for almost everything positive and punished for infractions. I excelled at academics, lettered in swimming and golf, acted in plays, wrote for the school paper, became an officer, and gained some self-confidence. During my infrequent trips home, where the misandry and belittling by my mother continued, that self-confidence was always put to the test. Young teenage boys are capable of an enormous amount of work, as in my case, and the three years of preparation at Shattuck School paved my way for admission to college and eventually graduate school.

Still, for the rest of my life I found myself searching for mentors and role models, which led to my writing about WWII heroes1. Why WWII heroes? Because it’s the age I grew up in. I had three uncles in WWII. Also because it was a just war, the last war duly declared by Congress, and we, the Allies, were the good guys. That generation of soldiers seems to me the most heroic. I think it is no accident that the greatest military leaders have the most character, and that great leadership is universal across the generations, the genders, and the spectrum of human endeavors, including business and politics.

The Final Minutes

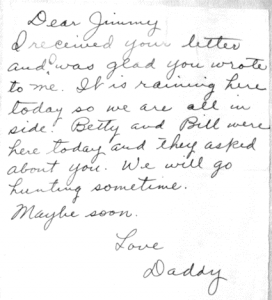

Daddy’s last letter, July 1942

I went back to Lake Osakis about fifteen years ago, and tried to reimagine my father’s death. After he landed in the water, he must have been disgusted to realize that his guns, other valuables, and any ducks were lost. Maybe he and Crandall cursed each other for whoever was deemed to be at fault. Although Carl was an excellent swimmer, he realized the futility of trying to disrobe and swim the quarter mile through the reeds to shore. Then after close to an hour of yelling and hearing no response, the gravity of the situation must have sunk in. Towards the end, if Carl were conscious enough to witness Oscar Crandall’s drowning, it must have come as the final horror.

Carl was a pretty spoiled man and used to getting his way. He had willingly defied death before and it used to be a game. Now the game was over—everything had gone sour. He was about to leave a grieving mother who loved him more than anyone in the world. He was also about to bid adieu to a grieving wife and three children: a 5-1/2-year-old girl; me, a 4-1/2-year-old boy; and a 7-month old baby boy. They would all suffer from his lost company, nurturing, and support. I still have the last letter he sent me. Did he think about me and his promise that we would go hunting sometime, maybe soon?

Dad as Role Model

Of course I’ve used an idealized version of my father as a role model. I gave myself permission to do the kinds of things he would have liked, including downhill ski racing, mountain climbing, wilderness canoeing, and motorcycle riding. However, though at one time I did some competitive target shooting, I never had the slightest desire to take up hunting.

Jim Sudmeier

Luck, WI

Summer, 2019

[1] Sudmeier, Jim. Patton’s Madness: The Dark Side of a Battlefield Genius, Stackpole Books, 2020.