“You’re going to be a guide for canoe trips at Camp Menogyn in the Boundary Waters,” said the 30-ish woman, barely looking up from her desk. Jane Andrews, Assistant Director. of Placement at Carleton College was not a fan, and I felt this would be payback for my previous year as a sophomore, when I pulled too many hijinks in the off-campus quasi-fraternity called Rice House.”

I didn’t doubt that Jane intended the Minneapolis YMCA wilderness Camp Menogyn on West Bearskin Lake, 33 miles up the mostly unpaved Gunflint Trail from Grand Marais, Minnesota, as a sort of purgatory. Located in Quetico-Superior country, it is possible to go by canoe from lake to lake with small portages from Minnesota to Hudson Bay. In any case, I was ready for it. It would be my first exposure to the wilderness — my first lengthy camping experience. I soon learned to love the challenge, the adventure, the fresh air, drinking water directly from the pristine lakes, chopping wood, finding the route with inadequate maps, cooking and baking for groups of people, getting into shape like never before, the relationships and friendships, the leadership experience, and building some rational self-confidence. I came back to college for my junior year, energized and rededicated to academic progress that would propel me into my future career.

Looking back, I can say without question that 1957 was the best summer of my life. Today I continue to enjoy canoeing. I honeymooned on a canoe trip, and my children and grandchildren enjoy canoeing. When we moved to California, my wilderness experience at Camp Menogyn inspired me take the Sierra Club Basic Mountaineering Training Course. For all these things I thank the Minneapolis YMCA, the Camp Menogyn Staff, who carry the torch and traditions of this magical place, and also, I thank you, Jane Andrews, for knowing a thing or two.

Shooting Saganaga Falls

Five foot Saganaga Falls. This is the portage for going around it.

The trip up the Granite River to Lake Saganaga was my favorite. My break-in trip was there under the capable tutelage of Norm Dahl. This bearded, grizzled veteran was totally confident, and full of information which he gladly passed on to me. I did the same trip subsequently once or twice in the summer of 1957, and perhaps one time in a later year. I remember the sun glinting off the waves in the big Gunflint Lake, and marveling at the beautiful house on the only inhabited island in Magnetic Lake, the source of the Granite River.

As a guide, obviously you had to be in front in most situations. I had a group of strong and rambunctious 15 to 17 year-olds who came up from Harvey, Illinois with their adult leader. Campers often tried to challenge me for the lead on open lakes. Sometimes they made a pretty good sprint, especially when they had three paddlers per canoe. Since my canoe carried the bread pack and the food pack, about 40 and 60 pounds respectively, I had only one paddler to help me. But usually the campers were erratic, their courses caroming left and right. I was six feet tall and weighed about 130 pounds, with enough wiry strength to paddle hard all day.

On the trip along the narrow Granite River, see-sawing across the U.S.-Canadian border, the rule was to never go around a corner or out of sight without ensuring the canoe behind saw where you were going. As I explained to the group, let me lead the way so you don’t miss a portage and/or get lost.

This is my group from Harvey, IL

One of the highlights of this river trip was Horsetail Rapids. To miss the rocks, you needed to execute a very sharp left turn. As Norm had demonstrated, the sharpest of canoe turns was made using a bow rudder, and I showed the group how to do it. Then came Saganaga Falls — a vertical drop of about 5 feet with large boulders perched along its edge. A few miles above the falls we waited for some stragglers. I asked the campers in the adjacent canoe to wait while I paddled upstream to find the stragglers. Eager beavers, however, they took off before I got back. Shortly afterward, we heard yelling up ahead.

As they told it, the lead canoe had discovered the falls too late. Somehow the canoe had gone sideways against one of the rocks on top of the falls, tipped sideways, filled with water, and the campers and their packs went over the falls. The water pressure wrapped the Grumman aluminum canoe around the rock, into the shape of a fortune cookie. I forget if the canoe went over the falls on its own, or if we had to pull it off the rock. But everybody and everything that went over the falls swam or floated to safety, unharmed.

I was very upset, but kept it inside. If we were to get home, we needed that canoe. On a flat piece of ground, while others held the canoe, I climbed upon the camel-like hump and jumped up and down. Little by little I bent the canoe back into shape, except for one problem — a foot-long, narrow slit in the aluminum bottom. With adhesive tape from the first aid kit, I closed the crack. Then after melting pine tree resin and spreading it over the adhesive tape, it formed a tough, waterproof seal. Nature’s epoxy. We continued on our way for the next week and had a fine trip.

Some of the 1957 crew. Me (2nd from left), Ted Gamelin (next to me), Tom Olson (5th from left), Norm Dahl (3rd from right), Rene Fournier (2nd from right), Phil Brain (right) (all standing), and Rick Scott (2nd from left, squatting).

Camp Director, Phil Brain, the dour veteran of the Bataan Death March, was understandably upset with me, and said that the patched-up canoe was to be my property for the rest of the summer. Fair enough, the damage was my fault. But the patch was amazingly indestructible, and lasted for the rest of the summer.

That fall, the group invited me down to Harvey, Illinois, and paid my bus fare for a reunion. They put on a banquet with a slide show and much storytelling. I bonded with that group, and stayed in touch for some years. We all derived an exceptional, positive experience out of what might have been a real downer.

Eaten by Bears

With each new group of 8 to 20 campers, aged 15 to 17, normally with one or more adult leaders, I spent the first day teaching them what to bring, how to get in and out of a canoe, how to paddle, how to portage, and how to right the canoe in the middle of the lake after capsizing. Normally there was also a break-in trip, paddling and portaging over two or three lakes. Then I planned the route for a trip of one or two weeks, got them equipped with tents, sleeping bags and air mattresses, I planned the menu, and packed the food. The bread pack was full of typical American “balloon” bread, such as “Wonder Bread” or “Holsum”. By compressing it lengthwise, we squeezed the air out of it, and it would keep pretty well for a week or two.

It usually took a few days to know the campers, and to judge, for example, if they were trustworthy. During July 13-20 I took a group of nine campers from the N.E. Minneapolis YMCA into an area east of Camp Menogyn where I had never been. After two days paddling (W. Bearskin, Clearwater- Mountain- Lily-Moose- No. Fowl- So. Fowl- Royal) we occupied a campsite at the east end of John lake.

Every third day was normally a layover day, and we pitched our tents and set up camp, expecting to be there for two nights. When I got up in the morning, the leather straps on the heavy canvas food pack had been opened, food was strewn about, and some of it was missing or partially eaten. At breakfast, I politely asked the group if anybody knew anything about it, or if anyone had heard anything during the night. Everybody denied knowing anything about it. I was not convinced, and wondered what kind of juvenile delinquents we had here.

During the day we took a side trip back to Royal Lake where we watched a bald eagle catching fish from a nest perched above the lake in a dead tree. We also climbed the 300 ft. cliffs to the east of Royal Lake. The rock was crumbly and I had to rescue two of the campers who had chimneyed up to a point where they ran out of handholds, and freaked out. They learned why down climbing is harder than up climbing. When we returned to base camp, two campers who stayed behind told us that a bear had come into the camp. The story seemed a bit suspicious to me, and I wasn’t convinced they they weren’t just covering their tracks from the previous night’s raid on the food pack.

So that night I prepared a “foolproof” scheme for preventing any further loss of food. With the bow of my inverted canoe sticking right into my tent, I placed the bread pack inside the canoe up on one of the seats. I placed the food pack up inside on the other seat. All my pots and pans, silverware, etc. were placed on top of the canoe so that the slightest motion would make lots of noise. I took the axe inside the tent with me, and went to sleep with the foot of my sleeping bag resting on top of the canoe, so that I would feel any vibration or motion. At last I could rest assured that our food was safe, and slept soundly.

When I awoke the next morning and unzipped the mosquito netting I could not believe my eyes. The canoe and kettles had not budged, but the food pack was on the ground, ripped open and food missing and scattered everywhere. The gap between the ground and canoe couldn’t have been more than 10 or 12 inches, yet the bear had reached under and removed the pack without disturbing anything — within 6 or 7 feet of me! No human could have ever pulled such a feat requiring such strength combined with dexterity. The bread pack, the bulkier of the two, was completely missing!! Following drag marks, I found the bread pack in bushes about 50 yards away, pretty much emptied. I felt sorry for not believing the campers, and apologized to them. This was the only campsite I heard of all summer which had a bear problem. Had I been forewarned, of course, I could have hung the food from a tree, or avoided the campsite altogether. The trip home was not short (Little John, McFarland, Pine, Canoe, Alder, East Bearskin, Flower, Hungry Jack, and W. Bearskin) and took two days. Everybody was hungry due to food rationing, and the final sprint on W. Bearskin lake was a mad dash for the mess hall and the Finnish bath.

In 2010, I made telephone contact with two of the campers, now both retired, who were on this trip. By coincidence, one of the two campers who stayed behind on our layover day, and who came face to face with the bear while looking up from a scary science fiction book, was Bruce Ahlquist. Bruce, now living in Woodland, CA, later became a Menogyn guide himself (’62-’65), then Asst. Camp Director (’66), and made a career as a YMCA Director.

I also spoke with Dave Vant, now living in Pine City, MN, who described the trip as a life-transforming experience. The wilderness experience has provided many of us with a route to self-discovery — adventure, some hardship, maximum physical exertion, self-reliance, the need to improvise, to think under pressure, teamwork, etc. And what a setting to discover peace and tranquility amidst the pristine lakes, the birches and pines, the call of the loon, spectacular sunsets, the gentle sound of waves lapping on the shore, and the wonder of aurora borealis expanding onto the canvas of a moonless summer sky!

Daisy Mae

One of my trips was for a group of 20 high school girls from Evanston, Illinois, and their chaperones. This prosperous Chicago suburb had a group of very attractive and sophisticated young women. All were pretty, but the one that attracted the most attention was a voluptuous girl with long, peroxide blond hair and beguiling brown eyes, who wore black, cutoff shorts that best displayed her long, shapely legs, and often went barefoot. I don’t recall her real name, but she instantly earned the nickname “Daisy Mae,” from the famous Al Capp comic strip, “L’il Abner”.

One of my trips was for a group of 20 high school girls from Evanston, Illinois, and their chaperones. This prosperous Chicago suburb had a group of very attractive and sophisticated young women. All were pretty, but the one that attracted the most attention was a voluptuous girl with long, peroxide blond hair and beguiling brown eyes, who wore black, cutoff shorts that best displayed her long, shapely legs, and often went barefoot. I don’t recall her real name, but she instantly earned the nickname “Daisy Mae,” from the famous Al Capp comic strip, “L’il Abner”.

The size of the Evanston group required two guides, Norm Dahl and me. The girls had a large undercurrent of joking and teasing going on, and five or six days of camping with them was a lot of good-natured fun. Then Daisy Mae cut her foot badly, probably going barefoot on slippery rocks. She was in pain and it looked as if she might need stitches. Although the trip still had a couple days left, at that point we were less than a day’s paddle from Camp Menogyn. The decision was made that I, the more junior guide, should take Daisy Mae back to Menogyn. I got her back safely to Menogyn that day, and she was taken to a hospital in Grand Marais. No more than an innocent flirtation occurred, probably because of my total ineptitude with the fairer sex at that stage, but the rumor mill was in full swing and the Camp Director regarded the episode with suspicion.

“Linc” Teaches Origami in the Kybo

Linc Ekman, a thirty-something schoolteacher, fairly short, with crew-cut and nearsighted with Coke-bottle thick glasses, was in charge of the camp food, equipment, and other supplies. Parsimonious in the extreme, Linc was an efficiency expert with the ideal personality for the job. I imagine him inventorying every piece of Government-surplus American cheese, counting every elbow of macaroni, and every prune in our Thunder Stew (more on that later).

“Linc”

Our outhouse at base camp, the “Kybo”, was a six-holer. On one of my visits, Linc and at least one other camper were sitting there. The usual rolls of toilet paper were gone. Instead the wall was lined with newly-driven nails from which hung strips of toilet paper. Each strip consisted of exactly 5 squares. Linc explained that he had determined, perhaps mathematically, that the optimal ass-wipe required exactly five squares of toilet paper.

Unbelievably, Linc topped it off with a live demonstration. First you fold it this way. Wipe One. Then fold this way. Wipe Two. Fold again, turn over, and Wipe Three. Now drop into hole. Voila!! You should not need any more paper this time. Try as I may, I have never been able to duplicate this feat of Origami. What happens, for example, if a careless finger should penetrate a sheet of paper? Do you start over, or is there a recovery procedure? I’m sorry I never asked Linc about the finer points of his theory.

We guides had to build a fire every morning, rain or shine, to make hot cereal and coffee. Every third day or so we served Thunder Stew, consisting of stewed prunes, apricots, and raisins. When this stuff kicked in, few campers were prepared for the sudden abdominal convulsions, and the need to evacuate with an urgency nothing could stop. With everyone heading for the woods at the same time, all using rolls of toilet paper, one can imagine the hemorrhaging of camp finances. Linc was a fine fellow with a sense of humor, and he did the best he could to keep our camping experiences affordable.

Hooking the big ones on Davis Lake

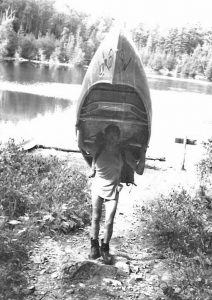

My most difficult trip of the summer was into Davis Lake from the south. This seldom-used portage was a half-mile long and overgrown with vegetation and fallen trees, with lots of marshy areas. The portage from the north is even longer. For my 130 pound frame, carrying one backpack, then boosting unassisted the 65 pound canoe onto my shoulders, portaging, even on well-maintained trails was always a chore. A portage of this length, however, while negotiating mud and trees fallen over the trail or just leaning enough so you had to crouch underneath was tough.

Skinny me, 130 lbs portaging 65 lb aluminum canoe plus backpack.

We had a nice group of campers, many of whom brought fishing gear because of the reputation of this lake for fish. This was also the only time I brought a rod and reel. After making camp on some granite slabs in the west end of the lake, we tried some fishing. Davis Lake was fished so seldom that the fish there were amazingly hungry and easy to catch. The only fish in the lake seemed to be Northern Pike, and mostly 5 pounds or bigger.

On one of my first casts using a Daredevil lure (red, white, and silver spoon plus treble hook), I hooked about a 5 pound Northern and brought him close to the canoe. Too bad I had run out of metal leaders, so it was easy for him to break my line with his sharp teeth. Luckily, I had another Daredevil, which I tied on, and on the first cast caught another 5 pounder. This time I was able to land the fish, and lo and behold, the fish had two Daredevils in his mouth, so I retrieved both my lures. Considering that Northerns hit because they’re angry, it’s not all that much of a coincidence.

The following was a layover day. I was fishing in the narrow west end of the lake and hooked into a really big Northern. I caught a glimpse and he looked like 10 pounds or more. There were tree branches submerged 5 or 6 feet visible below the surface. This wily old Northern just grabbed my line, dove straight down and basically tied a knot around a branch, causing me to snap the line.

Some of the campers were fishing directly from our campsite. While out in my canoe, I heard someone yelling ‘HELP’ from the campsite. When I got there, a young man about 15 years old was screaming in pain. He’d gotten a treble hook stuck in his index finger. The barb was embedded in the flesh, and the point of the hook was directly against the bone. As it says in all the books, push the hook straight through, cut off the barb, and remove the hook. The books don’t say what to do if the hook cannot be pushed through.

I looked in the First Aid kit for a razor blade. Nada. I asked around, “Did anybody have a razor or really sharp knife?” Nobody did. The sharpest knife I could find was the smaller blade on my own jackknife. Recall, we were several days from civilization via a tough portage, and no seaplanes or Medivac helicopters, not even motorboats, were allowed even if we’d had radios, which we didn’t. All I could do was cut — preferably quickly, before he went into shock.

I explained to the camper that we had to cut the hook out. He agreed. We laid him comfortably on the granite slab, and several of his buddies held him down securely by his arms and legs. As much as I hated to do it, I held the knife blade against his finger and CUT, CUT, CUT, CUT, CUT, CUT until the barb was fully exposed and the hook came out. The wound bled profusely, but we cleaned it with soap and hot water, and bandaged him up. The boy was brave, and greatly relieved to be unhooked. This was as close to being a surgeon as I ever hope to get. The boy’s finger healed nicely, and we finished a memorable trip.

Cooking Secret: Starved Campers

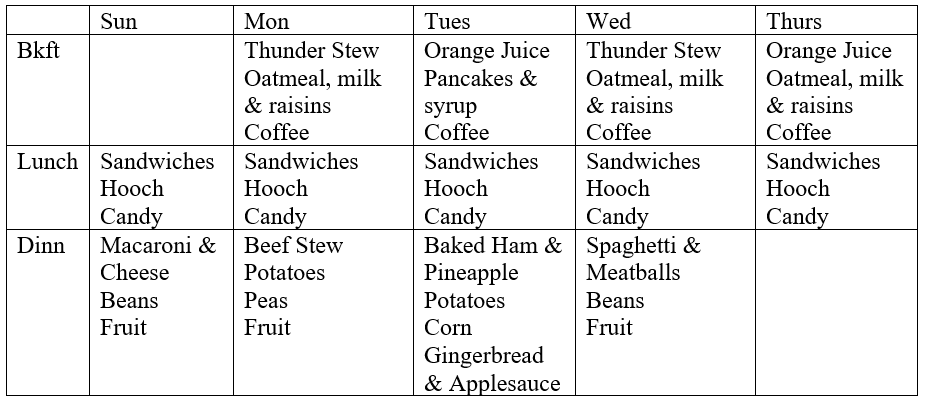

“If they’re hungry enough, they’ll eat anything” is something Menogyn guides probably all learn quickly. Campers in this situation often imagine guides to be tremendously skilled cooks. Here is a menu I recently found from a five-day 1957 Menogyn trip, complete with itemized food list:

Breakfast: Thunder Stew was made of dried prunes, apricots, and raisins. The milk was reconstituted from Carnation milk crystals. “Orange juice” was made from “Tang” powder. Brown sugar was available to sweeten the Oatmeal. Maple syrup came from a powder. Pancake mix was available in bulk.

Lunch: The guide’s canoe inverted and dried made the sandwich table. Salami and cheese, peanut butter and jelly, possibly with margarine seem to have been the choices. Hooch was just Kool-Aid made from powder. Chocolate and/or lemon drops were the candy.

Dinner: Beans, fruit, beef stew, ham or Spam, spaghetti sauce and meatballs, corn, peas, applesauce, and pineapple rings all came in tin cans. Pre-dating freeze-dried camping food, these cans are what made the food pack so heavy. Macaroni, spaghetti, instant mashed potatoes, and gingerbread mix came in bulk. Mustard and cloves were used to jazz up the baked ham and pineapple, made in the reflector oven. Everybody loved this meal, especially the freshly baked gingerbread covered with applesauce.

Gathering firewood and building a fire in every kind of weather was a challenge, but we could always scrounge enough branches or fallen trees of pine, even if we had to bring them in by canoe. When everything was wet, we tried to find birch, which would be dry inside if not too rotten. For baking, however, we needed cedar, perhaps the only wood that burned hot and fast enough. Somewhere on the lake we could usually find a dead cedar standing on the shoreline. Natural preservatives kept this wood from rotting for decades. Chopping the cedar down and felling it into the canoe diagonally and then paddling it back to camp was the usual method. It chopped beautifully and split nicely into strips about 24 inches long and 2 or 3 inches wide for use by the reflector oven. I’m curious to know, and a bit doubtful, whether such cedar trees are still available in 2020, and if so, whether it is legal to cut them for firewood. We certainly never had any permits for camping, and I don’t recall ever competing with anybody for campsites. Normally on a one or two week trip, we saw no other human beings.

A word about water. We never hesitated to drink the water without purification, especially while paddling in the middle of a lake. Close to campsites we would avoid heavily trafficked areas or places where people might have been swimming or washing dishes. I don’t recall a single case of distress known to be caused by bad water, and the term “giardia” was unknown to me.

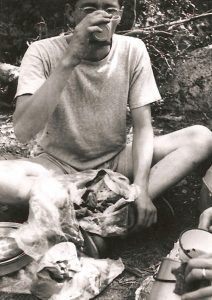

Author showing trail manners.

Trail Manners

When you cook at home today, you are careful to keep your hands clean. You pick up spills with paper towels. You clean or rinse out the pot you just used for boiling potatoes before using it to heat up the beans. You rinse the spoon used to stir one dish before using it to stir something else. When cooking in the Boundary Waters for a week or two without ever washing your hands or anything else on your body in hot water, without the luxury of paper towels, foggeddaboudit. You shift into another gear sometimes called “trail manners.”

You’re dead tired. You haven’t bathed for weeks, and you stink. Your hands are greasy, fingernails dirty, the black flies and no-see-ums infest your matted hair, the campfire smoke is blinding you, and a big thunderstorm is on the way. At some point you don’t give a damn. You just stirred the oatmeal. The coffee needs stirring. Clean the spoon? or get a new one? Naah. It won’t kill anybody.

You need to spread some peanut butter, but your knife is covered with fish guts. Ehhh. Just wipe in off on your pants. A hundred shortcuts like that save energy. A new perspective — social niceties jettisoned for survival. Feels right. Now you’re in the zone.

Nature Study in the Camp Dump

View of camp garbage dump from our stand.

We’d all heard that Camp Menogyn had a garbage dump on a hillside a few hundred yards away, and that it was often visited at night by bears. When you have two young guides, city kids raised in South Minneapolis, with time on their hands, does that sound like an invitation?

Tom Olson was my closest friend among the camp staff. Blond, blue-eyed, Scandinavian Tom was from Minneapolis, and had taught me about stereo, classical music, and the bawdy songs of Tom Lehrer. For some reason Tom and I were at the base camp for a few days with nothing much to do. I had a flash camera, and we thought it might be exciting to watch the bears and take their pictures.

At the dump we found an ideal spot for a platform high in an adjacent tree. We scrounged some boards and tools, and constructed the platform and a ladder. Then we began to worry about getting surrounded by bears, held prisoner in the tree, maybe eaten for dinner. Something was missing. An escape vehicle. We needed a BOSUN’S CHAIR!

The lake was some 20 or 30 feet below the tree stand vertically and perhaps 90 or 100 feet horizontally. If we could string a rope from our tree to one on the shoreline and ride an attached swing seat on a pulley, we could make our getaway by canoe. We found some ropes and a pulley. However, there were two pine trees directly in our path. About 6″ in diameter, we cut them with our axes as close to the ground as possible. We stretched the rope between our stand and one close to the lake as tightly as possible, and gave the Bosun’s chair its first trial.

The Bosun’s chair in action. Looks like Rick Scott, face frozen in panic, testing it out.

There were two minor flaws in the design. 1) a person’s weight made the rope sag so much that the seat barely cleared the tree stump, making castration a good possibility, and 2) when you got to the bottom, there was no way to stop. Nevertheless, the Bosun’s chair gave us a sense of security, and we tried our first photo shoot.

It had been dark for a long time, and it was getting cold in the tree stand. Finally we saw several bears, including two cubs waddling towards the dump. At the first sound of the shutter and the flash of the bulb, the cubs shot straight up an adjacent tree. In seconds they were above us. We didn’t feel safe anymore. I don’t recall exactly how we got out of there, but it was an experience that we didn’t repeat the experience.

The Camp Director was not pleased about our cutting down trees that tended to reveal the unsightly camp dump. He was right, of course, but by now, 63 years later, the trees have regrown and the camp has surely developed a modern system of waste management. All guides involved should get a plaque on the site for our contributions to this modernization. Perhaps even a commemoration of the Bosun’s chair (called a “zip line” these days) for use by visitors and staff with the disclaimer: RIDE AT YOUR OWN RISK!

Learn more about the remarkable fraternity of former Camp Menogyn Guides on yeoldmenogynguides.com

First draft January, 2010

Revere, MA