Why most gamblers are losers. I have never been interested in conventional casino gambling. The odds are stacked with corporate certainty against customers, who, for the most part, have no idea how the laws of statistics operate. For example, if you flip a coin and it comes up heads 19 times in a row, what is the probability of getting heads on the 20th flip? The answer: 50%. By similar reasoning, a slot machine that has paid no jackpots for an hour doesn’t owe you anything. The payout of slot machines ranges from 75% to 98%, but the average is about 90%.

Although some people claim to be consistent winners, they are delusional. While they brag endlessly about their winnings, they don’t account for their losses. The TV commercials show attractive, young people laughing and having fun while they gamble. What’s the fun of slowly draining your life’s blood into the casino? The reality is more like depressed, wrinkled, lonely old people smoking, drinking, and giving life one last roll of the dice. Delusion can lead to gambling addiction, which has ruined more than one life. In the long run the only winners have been the casinos.

In 1962 that situation was challenged by M.I.T. mathematics professor Edward O. Thorp’s book “Beat the Dealer.” For the game of blackjack, in some countries called “twenty-one,” Thorp discovered that the chances of the player winning become favorable at certain times, and those times can be predicted if the player is willing and able to count the cards coming out of the deck. When the deck gets “hot,” the player increases his/her bets and adjusts his/her strategies. Thorp verified his systems using computers, and proved he could win money in casinos.

Blackjack. For the uninitiated, let me briefly summarize the game of blackjack, the most popular gambling card game after poker. The dealer plays at a table against up to seven players. Your odds of winning are always better playing alone at the table (for one thing you may be allowed to play multiple hands). The minimum and maximum bets are posted on the table. First the players place their bets. The dealer shuffles from one to six standard 52 card decks and a player cuts the cards. The smallest number of decks gives the player the best odds. Then the dealer in clockwise fashion stepwise deals two cards face up for each player and two cards for himself, one face up and the other (the “hole card”) face down. All face cards have a value of ten, aces can be counted either as one or eleven (whichever is favorable to the player), and all other cards have their numerical value.

The object of the game is to get more points than the dealer, but never more than 21 (the player is said to be “busted”). If the player has 21 points from his first two cards, namely an ace and a “ten-card” (either a 10 or a face card), he has what is called “blackjack” and the dealer must pay 1-1/2 times the player’s bet.

After the initial deal, the dealer asks each player in turn if he/she wants another card (“hit”) or not (“stand” or “stick”) face up. This gives the player a chance to get closer to 21 points, but with a risk of busting. If the player busts, he is finished and the dealer collects the bet and the busted player’s cards. Then the dealer shows his hole card, and if he has less than 17 points, deals himself another card or more until he has at least 17 points. If the dealer busts he pays all bets an amount equal to their bets. If the dealer doesn’t bust, he settles with each player, some of whom win with more points than the dealer, and some of whom lose with less. If the player has the same number of points as the dealer (including both having blackjacks), it’s called a “push” and neither party wins. Then the dealer collects all the cards and, if there are enough cards remaining in the one to six decks, he deals a new hand, otherwise he reshuffles.

There are a few less frequent situations with names such as “splitting pairs,” “doubling down,” “insurance,” and “surrender.” Briefly, if you have a pair you can split it into a new hand (with a new equal bet) and play both hands. You may choose to “double down,” i.e. double your bet while taking only one more hit face down. If the dealer’s up card is an ace, you have the option as a side bet to buy insurance (up to half your original bet) against the dealer’s having blackjack, and sometimes you may surrender for a small side bet.

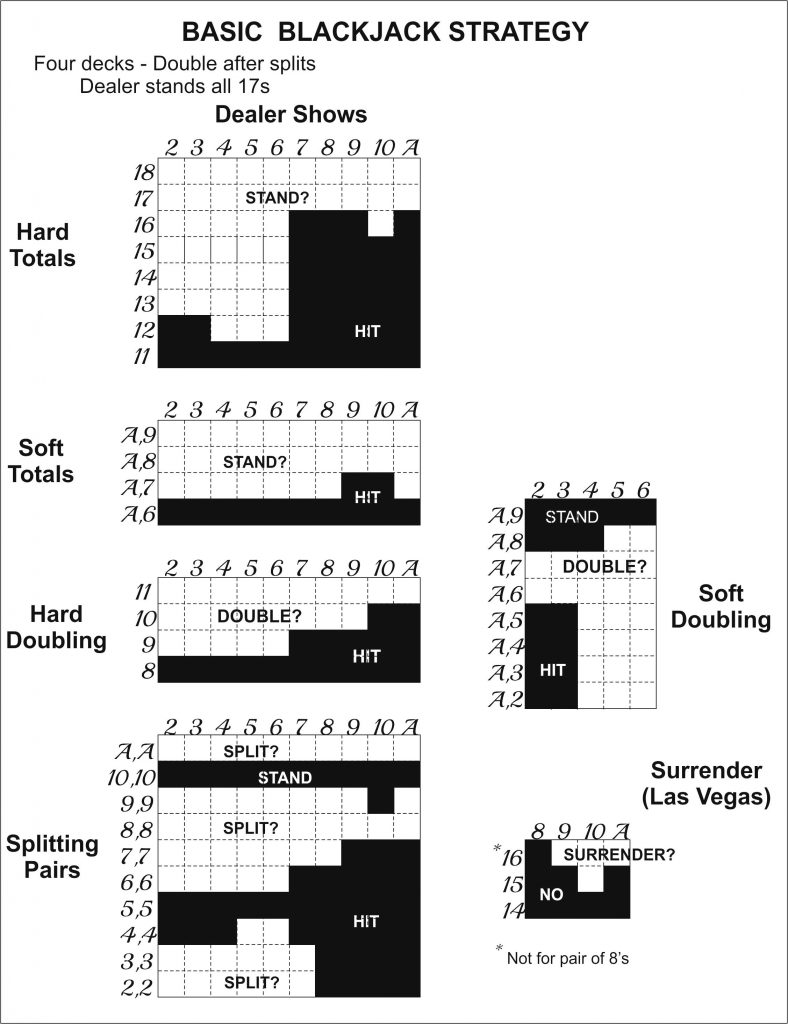

Basic strategy. Players must first learn the “basic strategy.” This is a set of tables you memorize for every combination of the cards you hold and the dealer’s up card. The tables are different for a “soft” hand, meaning one ace plus another card. Because the ace can count as either one or eleven, you can risk bigger hits compared to a “hard” hand without busting by counting the ace as one when necessary. There are also tables for splitting pairs and doubling down. (See basic strategy tables in Appendix A). The basic strategy does not involve card counting. It will simply enable you to play for hours, and more or less break even.

Card-counting systems. To earn money, one must take into account the cards that have been played. The important principle is that the deck of undealt cards accumulates a history. For a full table of seven players, at least 16 cards are played for every hand, more likely 22 or more. If most of the cards played are low numbers, then the remaining deck gets “hot,” meaning being richer in high cards (ten-cards and aces), which increases your chances of getting blackjack. If most of the cards played so far are high cards, the deck gets “cold.” In Thorp’s first card-counting system (the “five count system”), you only had to account for the fives. Then he devised the “point count” system and finally the “ten count” system. The HI-LO system devised in 1963 by Harvey Dubner is attractively simple to many, including me, especially for computational purposes. The running count starts at zero and is incremented by +1 for cards 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, and is incremented by -1 for high cards, namely 10, J, Q, K, and A.

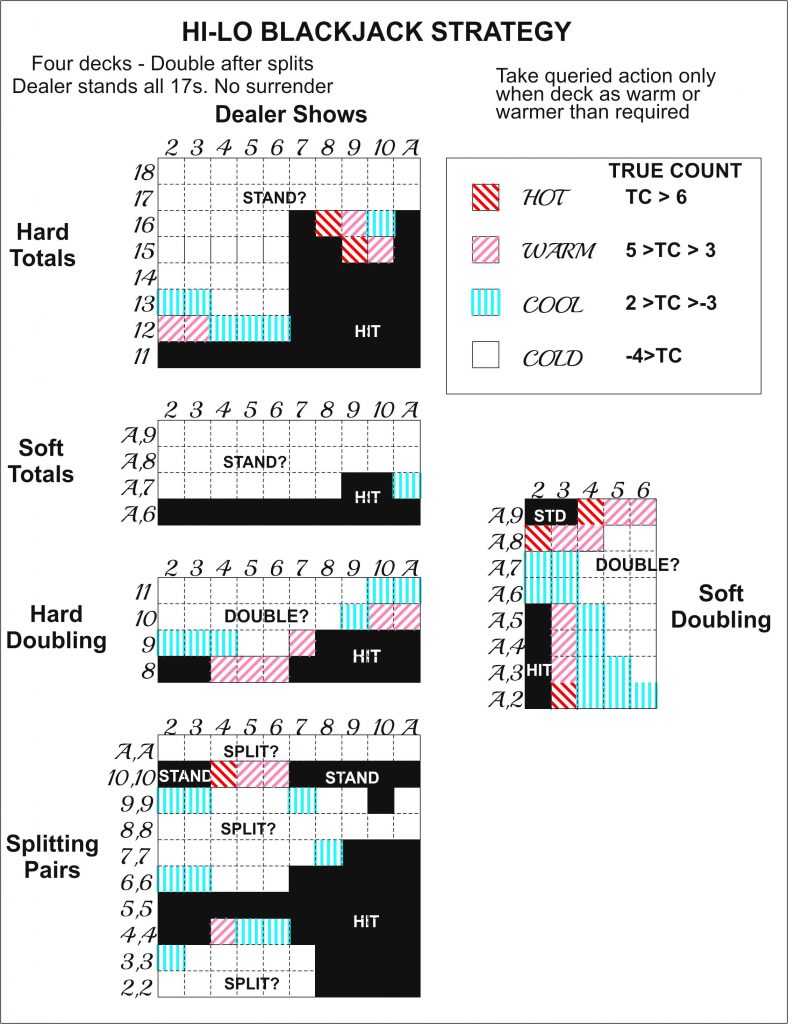

How hot is the deck? In the HI-LO system what you really want to know is the excess of low over high cards already played compared to how many decks are left. This is a ratio, obtained by division. True Count = (running count) / (number of decks remaining). When the deck is hot you increase your bet substantially and use an upgraded strategy from tables you’ve memorized. (See HI-LO system tables in Appendix B)

The fatigue, booze, “shills” and “smoke in your face” factor. There are blackjack players, including Thorp himself, who have the ability to sit at the table hour after hour, day after day doing this HI-LO calculation in their heads while remembering all the relevant strategy tables. I personally am not that good at doing rapid numerical calculations in my head, let alone multitasking. Meanwhile, players are being served free alcoholic beverages and distracted by “shills”, players working for the casino, the chatter of other players, and smoke inadvertently blown in your face.

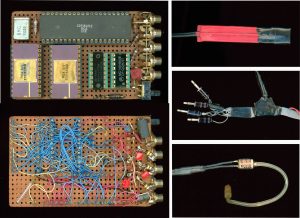

*Click to Enlarge* Photos of actual “Gizmo” parts: LEFT UPPER: Circuit board top view; RIGHT UPPER: Toe tape switch (one of two); LEFT LOWER: Circuit board bottom view; MIDDLE: Part of harness; LOWER: Ear phone

A concealed HI-LO calculating microprocessor. What if in the casino environment you could surreptitiously tap your right toe every time you saw a high card (10, face card, or ace) come out, and tap your left toe every time you saw a low card (2 thru 6) being played? What if a small computer in your pocket kept calculating the True Count, informing you with a tone in your ear? When if when the deck got hotter, the tone got higher in pitch? That, in a nutshell, was my idea in the early 1970’s for taking the tedium out of card counting, still leaving the player to make all the strategic decisions.

In the beginning I was working on an analog design using operational amplifiers (opamps), meaning voltages that go up and down instead of ones and zeros in the digital world. I found that for the input, various types of ribbon or tape switches would lie flat inside my cowboy boots (I was an “urban cowboy” in those days) and were easily triggered by my toes without making noticeable noise or motion. The audio output device was a miniature speaker made for use in hearing aids. With my long, brown hair at that time, the fine, dark enameled leads were strong but well concealed. In the mid 1970’s I met Earl, an expert in microprocessors, and with his help I designed and built the “Gizmo.” Earl was not a partner, simply working with me for pay.

Earl chose the microprocessor, an 1802 CMOS 8-bit unit in a 40 pin dual in line package (DIP). For added memory Earl used two 24 pin DIP 128 word 8-bit static CMOS ROM chips labelled CDP1823CD. The only other active units on the circuit board were a 2 MHz clock oscillator crystal for the microprocessor, a CMOS quad D type flip-flop (MM74C175), and a MOS hex inverter/buffer (MC14049UB). The latter two were 16 pin DIP packages used for conditioning the microprocessor inputs. All chips were in sockets connected by wire-wrapping. All this fit on a circuit board that went nicely into a cigarette case. There was an external battery pack of four AA batteries in series. There was an external reset switch to indicate every new deal of the cards, an external switch to change the number of decks, and an ON/OFF switch on the circuit board to preserve battery life. All units were connected by a ribbon harness and most went into my pants pockets with holes for the connecting leads.

“Gizmo”

Thus the microprocessor was driven by four external input switches (high, low, number of decks and reset). It produced one output, namely an audio signal of variable frequency. The assembly language programming was all done by Earl. I no longer have a listing of the program, nor do I have a schematic diagram of the Gizmo, but I still have most of the parts. Many card-counting systems have been developed over the years, including five count, point count, ten count, HI-LO, Hi Opt1, Hi Opt2, etc. Some might have been programmed into a microprocessor like this, but I preferred the HI-LO system. The fact that cards 7, 8, and 9 have not been included in the running count (or in the number of decks remaining the divisor) can be corrected by the approximation of bumping up the card totals 30% in the computer program (dividing by 40 rather than 52). It’s a lot better than trying to eyeball the number of decks remaining and doing long division in your head. Thus the True Count can be computed:

True Count = ( ∑ LO – ∑ HI ) / [No. decks – (∑ LO + ∑ HI) / 40 ]

Knowing the True Count, one can group the output into four recognizable tones: COLD, TC ≤ -4; COOL, -3 ≤ TC ≤ 2; WARM, 3 ≤ TC ≤ 5; and HOT, TC ≥ 6. COOL is the same a NEUTRAL or ZERO. A few strategies are different when the True Count is COOL instead of COLD, for example, making the distinction worthwhile. A good rule of thumb is to bet 1, 2, 3, and 4 units depending on the four tones, going from colder to hotter.

Legality? Would the “Gizmo” be legal? I was not aware at that time of any laws banning the use of such a device. Microcomputers were relatively new, and such a device may never have been previously used. But casino security was everywhere. Every player was constantly monitored on closed circuit TV, and photos of suspicious card-counting players were shared among casinos. The Pit Bosses also scrutinized the players, being especially watchful for “Perfesser types” like me in the new Thorp era. So I took every precaution to avoid detection and to insure that the legality of my device would not be adjudicated by casino heavyweights out in the alley behind the dumpsters.[i] My rationale, if caught, was that I, the player, still had to make the strategic decisions. The computer was a memory aid. The main question was, ‘Would the Gizmo actually work?’

Road testing. Las Vegas. Now it was time once again to confront the age old question, “If you’re so smart, why ain’t you rich?” Some of this part is a blur. I went first to Las Vegas by myself with little money, perhaps $400 or $500, hoping to get an idea if the Gizmo would actually win money for me under casino playing conditions. How well under pressure would I be able to remember the strategy tables I’d memorized, but had few hours of actual practice? Would I remember to split pairs, double down, buy insurance, take care of soft hands as well as hard, etc? I found the least expensive lodging in the downtown area. I surveyed the Fremont Street casinos for blackjack tables in my price range, i.e., one dollar or less minimum bets, and tried to find single deck games. Then I went back to the hotel for “suiting up.”

I put on the pants with holes in both pockets, threaded the battery pack through the left pocket and the computer through the right pants pocket. I put on my cowboy boots with the tape switches taped to the soles, and connected the foot switches to the harness I wore inside my clothing. The final task was threading the earpiece inside my shirt collar, hiding the wires in my long hair, running the speaker behind my right ear and bringing the thin plastic tube into my ear. I turned on the switch on the cigarette case and tested the foot switches.

After I’d played a few rounds, my knees stopped shaking and I took a break. There was no indication that anyone had noticed anything unusual. I gained more confidence and for the next few hours, as I bet more money in favorable situations, actually started to win a few bucks. I played until I was exhausted, and tried to get some sleep that night. The next two days I continued to play the various casinos, and ended up playing at tables with $5 minimum bets. I was quite tired after three days, and ready to get back home. I was proud to be ahead by maybe three hundred dollars, although I had to pay half of that for expenses. I felt that the computer was ready to go, except for a few tweaks here and there.

“Mr. Clean”

Reno. A few weeks later I wanted to try somewhere a little more relaxed than Las Vegas. I spent about two days in Reno and had about the same experience as far as earnings. That is, I made over $100, but most of it went for expenses. At least I was not losing money.

The most memorable part of Reno was the presence of a man I nicknamed “Mr. Clean” one afternoon at the Blackjack tables. Completely bald, muscular, with two large earrings, this man was playing at his own table, surrounded by a large crowd, including several gorgeous women dressed right out of Victoria’s Secret. He had about 20 large stacks of green chips, which I knew to be $100 chips. I guessed he had a total of maybe $30,000 to $50,000 in chips. He slobbered like an animal. When he spoke, he barked loudly, and got people to bring him food, drinks—whatever he wanted. Whether he won or lost, he generously tipped the dealer with the green chips. The Pit Boss was paying close attention to “Mr. Clean” who at one point threw three or four green chips at him with a grunt. The rest of the crowd seemed to feel like me — never having seen somebody with so much money to throw away just for the sake of feeling important. No doubt casinos love people like this and comp him generously with whatever he wants.

Carson City. On another trip either to gamble in Reno or to ski in Squaw Valley I passed through Carson City. Nevada was famous for having no speed limit, but on the south end of the town there was a speed trap, with a posted limit of 30 miles per hour that went on for many miles before you got to the town. I was driving a Datsun 240Z with a custom paint job, and a Nevada State Trooper started following me. I hadn’t seen another 30 mph sign for some time and I must have sped up a bit. Pretty soon the flashing red light appeared in my rear view mirror and this cop in a brown uniform with the cowboy hat and boots comes swaggering slowly up to my car like John Wayne. I rolled down my window. He stared at me and said, “Buddy, you’ve got a lead foot!” I forget whether he wrote me a speeding ticket or just a warning, but never forgot the incident.

Carson City. On another trip either to gamble in Reno or to ski in Squaw Valley I passed through Carson City. Nevada was famous for having no speed limit, but on the south end of the town there was a speed trap, with a posted limit of 30 miles per hour that went on for many miles before you got to the town. I was driving a Datsun 240Z with a custom paint job, and a Nevada State Trooper started following me. I hadn’t seen another 30 mph sign for some time and I must have sped up a bit. Pretty soon the flashing red light appeared in my rear view mirror and this cop in a brown uniform with the cowboy hat and boots comes swaggering slowly up to my car like John Wayne. I rolled down my window. He stared at me and said, “Buddy, you’ve got a lead foot!” I forget whether he wrote me a speeding ticket or just a warning, but never forgot the incident.

I stopped at a casino on the main drag of Carson City to get some lunch, and to practice a little blackjack. I was not wearing my computer, but after a few hands I was ahead by $65 when the Pit Boss leaned over to me and said “I want you to leave.” “What did I do wrong?” I protested. “Just get out, NOW!” I could not believe it. For only $65? Had I been behind $1000 I’m sure I could have stayed all afternoon. I began to doubt the validity of all card-counting methods. You can lose all you want, but as soon as you start winning, you’re kicked out ? After millions of elegant statistical calculations here is the proverbial turd in the punch bowl: the casino is private property. Looking back, it’s possible from the few weeks I’d been successfully playing blackjack that my photo had already gotten into circulation among the casinos. Edward Thorp himself had to resort to wearing disguises within his first few weeks.

The dreaded spoiler hole.

Bunny stuffing in Hawthorne. After a day of skiing at Mammoth Mountain, California, I was eager to play some blackjack. The nearest casino was in Hawthorne, Nevada, about 85 miles away. With little traffic on these desolate roads, I figured I could get there in one hour in my Datsun sports car. From Mono City to Hawthorne there was no traffic at all, and I could use that “lead foot” of mine. The road had been plowed, leaving about 3-4 foot vertical walls of snow on both sides. About half way to Hawthorne I saw something in my headlights. A big, western jackrabbit running fast. He couldn’t outrun me and he couldn’t jump out of the road, so, although I tried to slow down, there was a sickening Thump. I felt bad.

When I got to Hawthorne, I looked at the front of my car, and there was poor, dead Mr. Jackrabbit stuck in the spoiler hole, about 3 by 5 inches designed for cooling the brakes. His head, ears, and four legs were sticking out. The airstream must have sucked him by the butt into that small hole. Highly improbable –not very funny.

South Lake Tahoe. The last time I used my computer was in Lake Tahoe. I was reasonably confident by that time, had about $500 as a bankroll, and decided to play at $5 minimum tables. This was the make or break test for me. I lost a few hands, but kept on playing. Lost a few more. Then a few more. After losing 15 hands in a row, I felt “This is f**king impossible! I’ve never, ever lost 15 hands in a row before. Not fun!” I was tired and I quit, never to return.

How do you know if you’re being cheated? There are more ways for the house to cheat than a dog has fleas. For example, the deck may not be properly shuffled, leading to unfavorable hi and lo alternation. The dealer may “shuffle up,” i.e., shuffle the deck every time you substantially increase your bet. More importantly, you need a bankroll large enough to take care of any bad streaks. Rule of thumb: at least 150 times your minimum bet. I never had a big enough bankroll, and probably never would. Furthermore I had a full time career as a low-salaried chemistry professor. This little diversion into the blackjack world lasted only a few months. It was fun and exciting, but there was going to be no easy money, and it was time to end it. I concluded that I could make money playing blackjack, but that it would be a stressful, dangerous, minimum wage job in an unhealthy environment.

Team tactics. As detailed in the 2008 movie called “21,” it has been possible for skilled players using team tactics to make large amounts of money. The original MIT Blackjack Team had 6 players from MIT and Harvard who were highly skilled at card counting. To avoid suspicion when the card counters suddenly raised their bets, the MIT Team signaled an outsider (the “Big Player” or BP) to join the game whenever the deck got especially hot. Often loud, boisterous, and acting very drunk, the BP would place very large bets. Just by “luck,” BP won more often than he lost. In addition to card counting, at various times the group used advanced shuffle and ace tracking techniques. There were big investors, who earned as much as 250% return while the students were paid $80 per hour. Winnings have to be shared, and ideas of fairness can differ widely. Although this Team went on for a decade, and new teams still exist, the team approach introduces complications from rivalries, personality conflicts, and as always, stress.

Future technology. The advances in electronics and miniaturization that have occurred since 1977 are staggering. Anyone foolish enough to want to duplicate what we did could probably find everything on a single chip. Or using off-the-shelf products. Think of the smart glasses you can buy at Walmart for $42 that relay music through the temples to your ears by wireless Bluetooth. Or Apple Augmented Reality (AR) Glasses which could potentially replace the iPhone with both audio on the temples and video on the lenses. Imagine the computer power. But the casinos have experts too, and they may be sniffing the air in search of stray electronic signals emitted by unwanted foreign devices. And since 1985, any kind of artificial gambling aid is against the law, at least in Nevada.

Final thoughts. George Sawyer, one of the five founders of the MIT Blackjack team was interviewed Mar 27, 2018, on Quora.com. Here is his considered best judgement:

Quora: Is it possible to make a living playing blackjack? If you are in the US, and have a $10,000 or more bankroll, I think you can make about $35~$40 per hour playing blackjack. You can average something like a 1% edge on a bet. However there is a very real, very practical limit as to how much you can bet. If you play for higher stakes the casinos will notice you and ask you to leave. If you play alone, you will experience heart stopping streaks of losses and heavenly elation of winning streaks. Variance is a very real very normal part of play.

Playing blackjack is, in my experience, extremely dull, also quite stressful. My personal experience is that you can play error free for about an hour. Ideally you want to keep a low profile. This is also a limiting factor as to how many hours you can play on one shift in one casino. There is nothing about playing blackjack that the casinos don’t know, and most casinos will have someone who can count cards better than you can.

I’d like to add this: Remember, you would need about two of your peak playing hours to pay for your meals and lodging in most resort towns.

Jim Sudmeier

Luck, WI

April 21, 2020

APPENDIX A

The author cannot warranty that this is an optimal basic strategy. It was obtained by combining his best sources many years ago. Rules change with time, and vary from casino to casino. Meanwhile computer calculations become ever more refined. It is presented here only to illustrate a typical basic strategy table.

APPENDIX B

The author cannot warranty that this is an optimal HI-LO strategy. It was obtained by combining his best sources many years ago. Rules change with time, and vary from casino to casino. Meanwhile computer calculations become ever more refined. It is presented here only to illustrate a typical HI-LO strategy table.

ENDNOTE

[i] Upon writing this article in 2020, I discovered that our Gizmo was legal (I would have been somewhat more relaxed had known that in 1977), but after 1985 it would have been illegal in Nevada.

I also learned for the first time what other inventors have been doing in this field. In 1961 Edward O. Thorp, with help from M.I.T. Prof. Claude Shannon, the “father of information theory,” built the first “wearable” [i.e., concealed] computer for winning at roulette. It was an analog computer using toe switches and an audible tone output, which he tried out in a casino with modest success, hindered mainly by the fragility of the ear piece. It was about the size of a cigarette pack and now resides in the MIT Museum. See https://www.engadget.com/2013-09-18-edward-thorp-father-of-wearable-computing.html and the article published in 1998 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/2336885_The_Invention_of_the_First_Wearable_Computer

I also learned about Keith Taft, the fearless and ingenious pioneer of blackjack computers. He never got rich doing it, but he designed and marketed several blackjack computers starting in about 1970. Together with his son, Marty, their passion was to outwit the casinos, for which Keith did spend some time in prison. A double major in physics and music, Keith was an inventive genius who had previously worked for microchip pioneers Raytheon and Fairchild. His first blackjack prototype, “George,” was built in 1970, and weighed about 15 pounds. It had 2 toe switches on each foot, one up, one down, and indicated the count with LEDs connected by very fine, delicate wires to the upper eyeglass frames. One problem — the LEDs could be detected by reflections in his eyes.

Keith himself went through great winning and losing streaks. Then around 1976 came “David,” using the Z80 microprocessor, oriented towards team play (the Big Player making the big bets) with hand keyboards operated through holes in pockets and transmitters to signal the Big Player. Later came “Thor,” a computer to track the shuffling (and possible clumping) of multiple decks. One of his inventions involved networking players together with fine wires about 3 feet long. Then there were “Magic Shoes” in which 12 batteries, computer, and all were hidden in “Frankenstein” shoes. Later still there was “Narnia, the sequencing computer.”

Most spectacular of all was “belly telly,” a video camera concealed in a belt buckle for the purpose of seeing the dealer’s hole card. It was the satellite truck parked outside the casino that led to Keith’s landing in jail for a few months, and led in 1985 to the first Nevada law against all types of artificial gambling devices. All this got Keith elected to the Blackjack Hall of Fame. See the entertaining 2004 interview of Keith and his son Marty.

He died at his home in Elk Grove, CA in 2006.