- Folwell Junior High School (1948-1952)

Mr. Cogswell. I don’t remember his first name if I ever knew it, but he made a huge difference in my life when I took his class in Algebra in 1951-52. I can’t find anything about him on the web, let alone his photo, but he was a tall man with dark, balding hair. His face had a rather strict appearance due in part because he had a glass eye, as I recall. He stood erect, and seldom smiled — all business. But he could teach algebra in a way that was fun and easy to understand.

Mr. Cogswell. I don’t remember his first name if I ever knew it, but he made a huge difference in my life when I took his class in Algebra in 1951-52. I can’t find anything about him on the web, let alone his photo, but he was a tall man with dark, balding hair. His face had a rather strict appearance due in part because he had a glass eye, as I recall. He stood erect, and seldom smiled — all business. But he could teach algebra in a way that was fun and easy to understand.

I was very small for my age, an issue made worse by the fact that I skipped a grade in elementary school. I was a loner, undefended by friends. Being an easy target, I lived in dread of being “pantsed,” the ultimate humiliation of being captured by bigger guys and having my pants removed.

In my three years at Folwell, I had been quite bored with the watered-down curriculum — things like typing and folk dancing for both sexes, home economics for the girls, wood, electrical, mechanical drawing, and print shop for the boys. In English class we learned to say “isn’t,” rather than “ain’t” because it “sounds better.” Having two domineering women at home, mom and grandmother, and no father, I rebelled against my mostly old, matronly female teachers, and found pleasure in throwing spitballs and being a clown. My home room teacher, Miss Thomas, humiliated me in front of the class — “Don’t pay any attention to James. He’s just trying to get attention.” For months thereafter I was unable to speak in front of a group of people — I just swallowed, but no words came out. I got bad report cards from the women teachers, and straight A’s from the male teachers in the shop classes and in Mr. Cogswell’s algebra. Clearly I needed male teachers.

Realizing how hard I was working, Mr. Cogswell seemed to take a personal interest in me and we often chatted after class. He suggested that I apply to West Point, where I could get a free college education. Nobody in my family was talking about college, and none of the immediate family had graduated from college. Mr. Cogswell’s thinking probably led to my going next to a military high school, and he probably wrote a letter of support for my financial aid. The financial aid I received from anonymous donors at Shattuck School in Faribault, Minnesota set in motion everything else in my career mentioned in this Tribute. I’m sorry I never saw Mr. Cogswell again after the school year 1952. I will always love the memory of this man and the teaching, the confidence, and inspiration he gave me when I needed it most.

- Shattuck School (1952-1955)

Dr. Frank “Buzzy” Below, making a point in class.

Dr. Frank “Buzzy” Below. I took Senior English from Dr. Below in 1952-53, but I got to know him the year prior because he was the faculty advisor for the school newspaper, “The Spectator.” He appointed me Alumni Editor when I was a Junior, a role which I continued for two years. I wrote an article for the Spectator as a free-lancer my sophomore year about my astonishing discovery of a giant, leather-bound, gold leafed copy of Mein Kampf just sitting on a library shelf, a gift from Hitler to all his provincial governors (gauleiters). It had been captured by troops of alumnus Gen. Manton S. Eddy, who donated it to the school. I dug into the story, which produced an interesting article that must have gotten Dr. Below’s attention.

The weekly deadline for the Spectator was 8 o’clock Sunday night. I was always the last one to knock on his dormitory room door and submit my articles, just before the deadline. He had a grudging respect for me, and we got along. We also had to write compositions in all English classes, but, in the main, I credit my two years on the staff of the Spectator and also later on the yearbook, the Shad, under Dr. Below’s stern tutorship for teaching me to write.

I worked hard and was academically in the top 3 or 4 of my class. I earned the rank of 2nd Lieutenant in the ROTC battalion. I lettered in golf and swimming, and acted in a number of school plays. This record earned me a 4 year full General Motors Scholarship to Carleton College. None of that would have been possible without the excellence of Shattuck School, the financial aid I received, and the dedicated Masters like Dr. Below and many other staff and faculty members, including the five mentioned next.

Honorable mention to five additional Shattuck Masters.:

Edward V. “Nails” McNally taught sophomore English and he was tough as nails. His specialty was grammar and diagramming sentences. Many in my class had been at Shattuck for a year and had a good background in grammar. I had to put in extra time and struggled to keep up. Prepositional phrases, predicate nominatives, subjunctive cases, adverbial clauses, objects of the preposition, we went on and on. No longer did things have to “sound” right, they better be right. I can truthfully say I learned everything I ever needed to know about grammar and sentence construction for the rest of my life as a 14-15 year old in that class. Thanks to the wonderful drilling of Edward V. “Nails” McNally.

James M. L. Cooley taught French, of which I took 2 years at Shattuck. With 13 or so students per class we got a lot of individual attention. With flash cards we memorized tons of irregular verbs. After an additional year of French in college, I was able to pass the reading exam for the Ph.D. at Princeton, although my conversational French was lacking. Trying to converse in French with strangers I sometimes had to resort to paper and pencil. Nevertheless, Mr. Cooley was a very kind, patient, and gentle man, with whom I developed a warm, paternal friendship.

Kenneth Agerter taught me Chemistry. He loved to do explosions and other attention-getting demonstrations. This is something I adopted as my own specialty in chemistry lectures at the University of California. I was quite advanced in chemistry, so found the course pretty easy.

Gerald Kiefer taught me Physics. I had to work harder at Physics than Chemistry, but did all right. Before Kiefer came to Shattuck he taught Physics in the Dawson, Minnesota school system. Coincidentally, there he also taught Physics to my first cousin once removed Roald Wangsness, who later worked on the atomic bomb during WWII, and became a professor of Physics and the University of Arizona. Both Physics and Chemistry were laboratory courses.

Nuba Pletcher was a kind, gentle, older man who taught me a year of American History. It was a good course, covering all the important events. He also required us to subscribe to Time magazine — a habit which I have maintained to this very day.

- Carleton College (1955-1959)

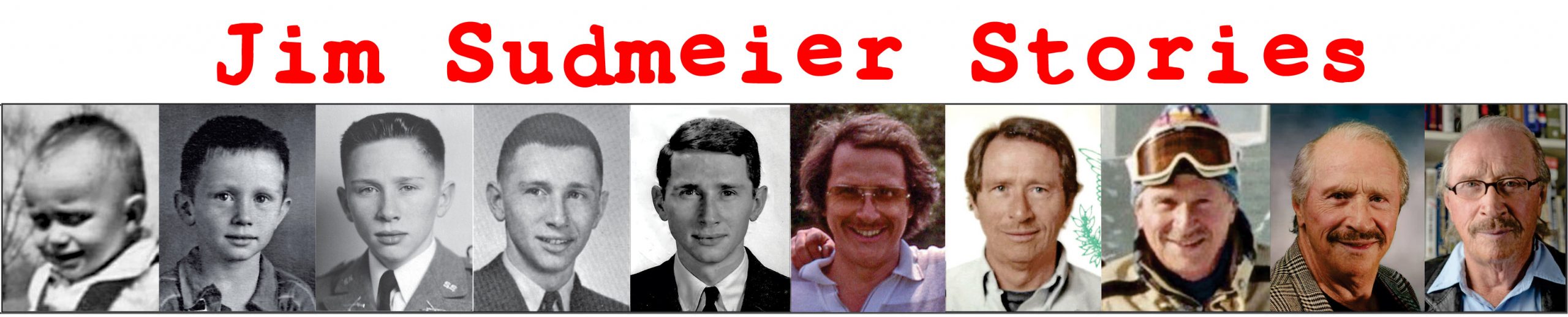

Me and Ramette with shaker box.

Richard W. Ramette. Dr. Dick Ramette was a relative newcomer to Carleton when I took his course in Quantitative Analysis. Tall and good looking, he radiated charm and confidence. His lectures were mainly on acid-base and other chemical equilibria. Some physical chemistry of solutions was included, such as Debye-Hückel theory. His exams were rigorous and exacting, earning him the nickname “Tricky Dick.”

I was a Chemistry Major, who had come to Carleton on a “3:2” program with M.I.T. I was supposed to spend 3 years at Carleton getting a B.A. in Chemistry followed by 2 years at M.I.T., after which I would be awarded a B.S. degree in Chemical Engineering. In my first meeting with Ramette as my major advisor, he changed the course of my life. He said, “You don’t want to become a chemical engineer. They’re just glorified plumbers. You want to stay at Carleton for four years and become a Chemistry major.” “Oh,” I said. “Okay.”

In my junior year I began doing independent research with Dr. Ramette. It was a project to determine the solubility of a salt known as copper iodate vs ionic strength in water and heavy water and to study the solvent effect. I wrote my senior thesis on the project, and gave a prize-winning talk at a regional college research competition. I learned well from Dr. Ramette how to do painstakingly careful research, how to write a research paper, and how to give an effective oral presentation.

Me and Ramette, together again, October, 2019.

Dr. Ramette regarded my work highly and wrote me a letter of recommendation for the Analytical Chemistry Ph.D. program at Princeton University, New Jersey. As I told the 92 year old Ramette during our recent reunion in Green Valley, Arizona, “Doing research with you changed my life. For my career I owe you everything.”

Honorable mention:

Dr. Martin Eshleman of the Philosophy Dept. By taking his course in Ethics, I nearly became a philosophy major. A person with a very underdeveloped sense of ethics, I was a curious case for the very dapper gentleman, Prof. Eshleman, always dressed in tweeds and penny loafers. In class one day, after one of my questions, he publicly labeled me a “naïve realist.” That is a person who doubts the existence of abstractions such as truth, liberty, justice, etc. Wow! What a mess I must have been! Twice he invited me for dinner in his apartment, where we had lively discussions. I realized that prospects for making a living philosophizing were going to be very slim, and stuck to the chemistry major.

- University of North Carolina (1961-1966)

Prof. Charles N. Reilley. I continued research with Dr. Ramette during the summer of 1959 after I had graduated. Ramette had organized an NSF Workshop for bringing chemistry teachers up to date with the latest research. Among his expert speakers was Charles Reilley from UNC. I was designated to help Reilley organize lecture demonstrations, and I made up his solutions. His topic was Chelometric Analysis of Metals. EDTA was a compound developed in Switzerland which formed very tight complexes with most metals, some with binding constants of ten to the 25th power. Reilley showed how certain colorimetric indicators could create sharp titration end points. Using a wide array of clever tricks such as “masking,” he showed how mixtures of metals could be handled one at a time. We enjoyed working together some hours in the lab.

Prof. Charles N. Reilley. I continued research with Dr. Ramette during the summer of 1959 after I had graduated. Ramette had organized an NSF Workshop for bringing chemistry teachers up to date with the latest research. Among his expert speakers was Charles Reilley from UNC. I was designated to help Reilley organize lecture demonstrations, and I made up his solutions. His topic was Chelometric Analysis of Metals. EDTA was a compound developed in Switzerland which formed very tight complexes with most metals, some with binding constants of ten to the 25th power. Reilley showed how certain colorimetric indicators could create sharp titration end points. Using a wide array of clever tricks such as “masking,” he showed how mixtures of metals could be handled one at a time. We enjoyed working together some hours in the lab.

Baby-faced, chubby, the chain-smoking Reilley with nicotine-stained hands, was outgoing, friendly, and charming. He smiled and winked. A life-long bachelor, he traveled everywhere with his aging mother, a retired, somewhat deaf, school teacher from Charlotte with a heavy southern accent. “Ahh jes luuv Chap-el Huy-ill,” she would say.

I was very impressed with Reilley’s personality, his brilliant mind, his achievements in diverse areas, and the fact that he was almost the only contemporary Analytical Chemist elected to the National Academy of Sciences.

After I’d been at Princeton for two years, I passed all course requirements, passed two foreign language exams, and passed the grueling General Exam (both written and oral). I had begun a research project with Dr. Clark Bricker that had no chance of success. When Dr. Bricker left Princeton, partly because of their phasing out Analytical Chemistry, I had the option to do my Princeton Ph.D. research at any other institution. I knew exactly where I wanted to go. To UNC to work with Charles N. Reilley. He was happy to have me and offered me a Research Assistantship.

Reilley himself had gotten his Ph.D. from Princeton, studying under the legendary N. Howell Furman. In three years with no summers, he had published 11 seminal papers on electrochemistry and spectrometry. As a teen-ager, Reilley had learned how to troubleshoot and repair radios (like another genius, Richard Feynman). It must be great training! Looking for a constant current source (CCS) for his electrochemical studies, and finding batteries insufficient, he made the revolutionary step of building a CCS using vacuum tubes. It was unusual in the early 1950’s to find electronic instruments in a chemistry lab. Instead of the old reliable polarography, current vs. voltage, Reilley introduced the variable of time. Using the new dimension he devised chronopotentiometry and amperometric titrations. His paper on tristimulus colorimetry was also devised in order to unify many principles of colorimetric indicators. His scientific innovations often arose by his understanding of the underlying principles in greater depth than competitors.

Being an Analytical Chemist gave Reilley license to move to the techniques where the greatest breakthroughs were happening. He liked to “scoop the cream off the top” in new fields. His research group at Chapel Hill when I arrived was involved in electrochemistry, gas chromatography, and calorimetry of metal complexes. He would give a new student a project, fully support the project, and let him go for months or years. When a project caught fire, he spent his energy getting it finished and written up. No progress, no Reilley. I was interested in the “chelate effect.” What gave metal-EDTA complexes their extraordinary stability, and the protonation scheme of EDTA? For higher sensitivity, I designed and build an isothermal microcalorimeter. It involved our machine shop and my gold plating, and glassblowing. I built a high vacuum rack. Mercury got spilled all over the lab when a flask containing a reservoir of mercury imploded. One and a half years went by with no calorimetric measurements.

Then I got interested in the department’s Varian A-60 NMR spectrometer. It had been monopolized by the organic chemists. They employed organic solvents such as deuterochloroform that gave no interfering proton signal. They told us we couldn’t run NMR spectra in water or heavy water solutions. Well, we tried, and it was possible. Suppression of the residual water signal got better with time, and my entire Ph.D. thesis consisted of pH titrations of polyprotic acids. Data processing required FORTRAN computer programming for lineshape analysis and non-linear least squares analysis using an IBM mainframe. I was Reilley’s first student to use NMR spectroscopy. The entire field of NMR of biological molecules in water laid before us in 1964.

Dr. Reilley got interested in understanding electronic circuits and devices by means of LaPlace Transforms. He taught a special topics course on it with his entire group, about a dozen of us, in attendance. Each of us was tasked with writing a chapter of a final NSF report, and I wrote a 15 page chapter on Servomechanisms — a great experience which prepared me for more electronics work and certainly for Fourier Transform NMR when it arrived soon thereafter.

Expecting to be finished by the summer of 1964, my wife and I planned a ten week trip, my first to Europe. We bought a new SAAB station wagon in Oslo, drove all over Europe and slept in the car. Frommer’s “Europe on 5 Dollars a Day” was our bible. We visited Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Holland, Belgium, Germany, France, Austria, Switzerland, Italy, Yugoslavia, and back to Norway to ship the car home. There was an international symposium on Coordination Chemistry in Vienna which I wanted to attend. Dr. Reilley and his mother also attended it. We were treated to an orchestra in the palace playing Viennese waltzes and we tasted the new wine in Grinzing, where I sat next to Nobel Prize winner Manfred Eigen, with whom I explored a possible Post-doc. After the conference, the Reilleys rode around with us for a few days in Austria and Germany. As our personal relationship had grown, it was wonderful to enjoy Reilley’s company and his trust.

My wife, Maud, & Dr. Reilley at Eagle’s Nest.

One day we toured Berchtesgaden, high in the Bavarian Alps, where Hitler once lived. We took a yellow postal van up the mountain called Kehlstein to the parking lot where you take a very grand, polished brass elevator, whisking you to the mountain top Hitler’s “Eagle’s Nest.” It’s very impressive and you get an amazing view of some of the highest Bavarian Alps.

That night we stopped at a cozy, rustic inn where the innkeeper, a plump, rosy-cheeked woman in a traditional Bavarian costume showed us to our rooms. Mrs. Reilley didn’t understand that not everybody understands English, so she just kept speaking louder till she thought they got it. The innkeeper looked very cute in her costume. Mrs. Reilley said to her, “Y’all cute as a button.” When the woman didn’t understand, Mrs. Reilley kept repeating it. Finally, she walked up to the woman and put her finger on one of her dress’ buttons and said it again. It was no use. Then Mrs. Reilly wanted to tell the German woman where we’d been that day. She pointed up the mountain and said “Hitler. Today. WE WENT HITLER!” Repeatedly gesturing upwards. By now the innkeeper was getting really baffled. She smiled, said “Gute Nacht,” and disappeared.

Dr. Reilley was always accepting of me, never judgmental. I really loved this man, and his sudden death of a heart attack at age only 56 was tragic, an event at home that almost killed his bed-ridden diabetic mother, who went without food or insulin for several days. With his lifelong friendship, good will, and recommendation, I was hired for an academic job at the prestigious Chemistry Department at UCLA in Los Angeles, California. There were several Nobel Prize winners in the department, and suddenly I found myself in the major leagues.

- UCLA Chemistry Dept. (1966-1971)

Frank A. L. Anet.

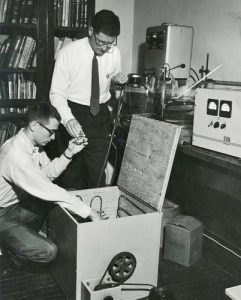

Prof. Frank Anet and some of his NMR gear.

While my Ph.D. from Princeton was not final, I spent the first year at UCLA as “Acting Assistant Professor.” Actually I was a Postdoctoral Fellow in the NMR lab of Prof. Frank Anet. Originally a natural products chemist, Anet grew up in Australia, but did his graduate work in France. He was a world-leading expert in conformational analysis of organic ring systems, and he studied them by extremely low-temperature NMR. For example, he froze out the inversion of cyclohexane at -60 degrees Kelvin, using his home-made low temperature probe, and determined the energy barrier. He studied many additional families of organic ring systems as well as natural products.

A generous, quiet, highly creative man, Frank was an expert in electronics and physical organic chemistry, and taught me a lot. His home-made spectrometers were assemblies of various components, such as r.f. amplifiers and frequency synthesizers. There was no manual like we had for the Varian A-60. When superconducting magnets became known, Frank was right there building his own. His student and my sometime collaborator, Craig Bradley, wound his own magnets from niobium/tin wire, built his own probes, and eventually became a top expert working for Bruker Instruments in Germany. Thus when I wanted a multinuclear large-sample spectrometer of my own at UCR a few years later, I had little hesitation about building my own iron magnet NMR spectrometer and probes with the help of a graduate student, Phil Curb, and some blueprints from a former Princeton classmate, Adam Allerhand of Indiana University.

I took this education in Physical Organic and applied it to Inorganic chemistry, namely metal-chelate ring systems. This tied right back to my EDTA complexes, which I extended at UCLA together with my graduate students. When I spent part of a sabbatical at Oxford in 1973, I was more fluent in conformational analysis than my host professor, and thus didn’t learn much about that, though I did get an education in the use of lanthanide (rare earth) paramagnetic probes for biomolecular structural analysis.

Honorable mention:

Prof. Robert L. Pecsok, Vice Chairman of the UCLA Chem Dept, was an Analytical Chemist and a big fan of Dr. Reilley. The silver-haired, handsome, Harvard summa grad and combat WWII Navy veteran made a home for me at UCLA. He even lent us a spare house with an orange tree in Pacific Palisades overlooking the ocean to live in for a few months while we got established in L.A. He threw a party at his home to introduce me to colleagues, such as Paul Boyer. I asked Boyer if he was an organic chemist. “No,” he said, “I’m a biochemist.” I probably should have known more about the prolific book editor and future Nobel Prize winner. Bob Pecsok was like a father figure to me and gave me all the support he could in a department that was determined to phase out its Analytical Chemistry program.

- UCLA Physics Dept.

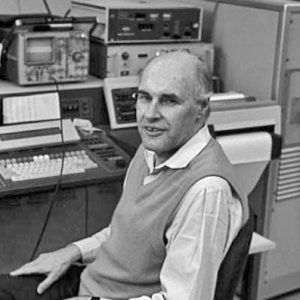

Marvin Chester

Prof. Marvin Chester. Not all my mentors were chemists or professors having a direct bearing on my professional advancement. Some influenced me in other ways. I met Marvin somewhere on the UCLA campus, or perhaps it was at a party. Seven years older than me, Marvin was a full professor of Physics who immediately stood out as different in appearance, speech, and actions. Marvin had a certain flair. Always fashionably dressed, Marvin was about happiness, acceptance, relationships, feelings, and quality of life. In comparison, I was a robot–a man in harness, spending most of my time and energy on professional advancement, yielding little satisfaction. Marvin was a human being. I was primarily a human doing.

Like his Ph.D. thesis advisor at Cal Tech, Nobel Prize winner Richard Feynman, Marvin was a Jew from New York City. Both had boundless energy, creativity, curiosity, and zest for life. Both experimented with drugs. Both had three marriages.

At the time I met him Marvin was between marriages. He was dating a “Go Go” dancer in her twenties. He lived in a small house secluded in one of those canyons north of UCLA– I think it was Laurel Canyon. The bell-bottom trousers, the hats, the scarves were not like other professors his age. His speech was laced with the popular expressions of the day — “Wow!” “Far out!” “It blows my mind,” etc. He showed that a person could be a professor without being a prisoner of the role. He was perfectly free and unapologetic about being himself. I suspected earlier what I read recently in his will, “I had very loving and caring parents.” We all feel about ourselves what was mirrored by our parents.

During the few years I hung around with Marvin, I was unhappy both with my career and with my marriage. One day, Marvin said to me straightaway, “Jim, you are ready for a divorce!” It was shocking to hear, because the thought had never come to me so directly. I knew that he said it out of genuine empathy and concern for me. One day I was riding in Marvin’s car along a freeway in L.A. and he started driving slower and slower. I asked him why he was driving so slowly. He said, “When I’m stoned I always drive slow. So driving slow makes me feel stoned.”

Marvin was a true intellectual—a person who is fully alive in a world of ideas. His research interests included quantum mechanics, helium superfluidity, symmetry, investment strategies, and population dynamics. He predicted and demonstrated a Bernoulli Effect in the electron gas. He is perhaps best known for his textbook “A Primer of Quantum Mechanics,” connecting the math to its philosophical underpinnings. But his interests were far broader than physics. For several years, he ran a discussion group of like-minded friends who met monthly at someone’s home to discuss topics already researched and presented by one of them. Called the “Concept Exchange Society,” they covered things like astronomy, cosmology, mysticism, information theory, spiritual values, linguistics, and consciousness.

You have to see his website “chesters.org/marvin” and his blog “divineneutrality.org.” These websites embody the spirit of Marvin Chester and I confess it was the inspiration for my present website. Check out his paradise home in the Redwoods under JOY ROAD/OCCIDENTAL or basic number theory in his blog under The Borders of Understanding. His lectures are animated and interactive, lovingly prepared by the consummate teacher. Skip around. You can learn some physics and expanded your mind. Though Marvin died in 2016, his soul lives there. I’m full of admiration and thanks to Marvin Chester for his kindness to me and his example of how to be a professor and still live a full life. As stated on his website, “He lived life to play and to learn. His heart was full.”

Honorable mention:

Herb Goldberg. When I read his book, “The Hazards of Being Male,” I was going through one of my mid-life crises. This book spoke to me very directly about men in harness, and I was pleasantly surprised that I was able to reach him on the phone and make an appointment for counseling. He is a wonderful guy with astonishing insights, and after about four two-hour sessions, including one with the girlfriend who was dumping me, I benefited a great deal, for which I thank him.

John Bradshaw. Another author (“Homecoming”) and star of several PBS lecture series on the family, addiction, co-dependence, inner child, parenting, meditations, etc. I read most of his books, and attended one of his Workshops one weekend in the Berkshires of western Massachusetts. It was good to meet him in person and to spend hours listening to him. He contributed greatly to my self-understanding, and my ability to grieve, to heal, and to feel, for which I thank him profusely.

- University of California at Riverside (1971-1984)

Prof. David R. Kearns.

Prof. David R. Kearns

When I came to UCR in 1971 as an Associate Professor in Analytical Chemistry, David Kearns was a full Professor of Physical Chemistry. He is three years older than me. We never collaborated in research, but became great friends. A graduate of UCBerkeley, David was doing various kinds of visible and UV spectroscopy. Then he discovered the magic of NMR during a sabbatical under Bob Shulman at Bell Labs in New Jersey. With a sample of transfer RNA (t-RNA) and a wide proton spectrum of some 20 ppm in a superconducting magnet, they made the very exciting discovery of the low-field (13-18 ppm) spectrum of protons involved in Watson-Crick base pairing. The spectrum was quite featureless because the t-RNA was a mixture of about fifty similar t-RNAs. Our colleague, Brian Reid, from the UCR Biochemistry Department, on the other hand, was skilled at producing large amounts of highly purified t-RNA samples, and a Kearns/Reid collaboration sprang forth. Brian Reid and his student Dennis Hare attended my one semester special topics course on “Biological NMR” to help get them get up to speed in this new area.

I was personal friends with both Brian and David, going with our wives to the same dinner parties, etc. I was in Oxford in 1972-3 when the three of us went out for lunch, and I could see their partnership falling apart. Both Reid and Kearns wanted to obtain their own NMR spectrometers and David had other sources of fractionated t-RNAs. Reid received an attractive offer to move to the Univ. of Washington in Seattle, and Kearns had an equally attractive move to UCSanDiego, where before long he became Chairman of the Chemistry Dept.

A slalom practice at Snow Summit, CA

The three of us had once gone skiing together at Big Bear in the local mountains, riding in student Bud Jenkins’ bakery truck (with “Eagle Bakery” printed on the side) and exhaust leaking inside from the fractured tailpipe. There were no seats in back so we sat on the floor. Dave loved to ski fast and so did I, and we became serious ski partners. We participated in numerous Far West Ski Association (FWSA) slaloms in Mammoth Mountain, California, and June Mountain, where David and his family had an A-frame. Some of these races were on steep, unpacked slopes. Bushel-basket-size holes began to form next to slalom poles, and sometimes we fell more than once getting to the bottom. A very aggressive guy named Bill DeHaas won almost every race, and we fantasized about dethroning him. We had our own bamboo slalom poles and set up practice courses wherever we could. Once we attended a week-long Ski Racing Camp in Bear Valley, California.

Sometimes I would stay as a guest in their June Lake cabin of the Kearns family, including David’s wife, Alice, his son, Michael, and daughter, Jennifer. Dave was an automobile collector, and had an old MG sports car and a Bentley sedan with an unusual suspension on whale blubber sewed into leather pouches. The family moved into a sprawling, large house in La Jolla, where David and Alice always gave great parties. Dave kept in shape running and playing handball. To me, Dave was a model of the successful chemistry professor. Brilliant, good looking, a fierce competitor, with a sense of humor and all the social graces.

After I had moved to Boston, Dave continued making ski trips with other friends to various ski areas, including some in Europe. One day skiing in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, in the mid 1980’s on a new pair of skis he took a very hard fall that injured his neck. The next day he was back in La Jolla and suffered a stroke which destroyed his ability to speak, and paralyzed him on one side. It has taken years for him to regain part of his speech and the ability to walk, and he was forced into early retirement in the midst of a very productive career. He hears and understands everything, remembers everything, and is fully conscious — the main problem for him is producing intelligible speech. His wife, Alice, passed away from a sudden illness some 10 years ago. David has had some bad luck, but I have never seen him exhibit the slightest trace of self-pity.

This fall, November, 2019, Jilly and I had a reunion with David at his apartment where he lives comfortably with his small dog near the beach in La Jolla Cove. David’s daughter, Jennifer, is a very successful lawyer in San Diego, and his son, Michael, is a brilliant professor and author of mathematics, algorithms, game theory, and investment strategies at the University of Pennsylvania. With Jennifer’s help, we went to a very nice Italian restaurant in La Jolla, and the four of us had a memorable evening. I really love Dave, who will always be one of my role models and heroes.

- Francis Bitter National Magnet Laboratory at M.I.T. (1985-1990)

Dr. Malcolm H. Levitt

When I first came to Boston in 1985, freshly bankrupted and uprooted from my California friends, I needed friends. Dr. Malcolm H. Levitt, a new Post-doc at M.I.T.’s National Magnet Lab was also open to friendships and we became good friends until he moved away in about five years. Right out of Ray Freeman’s lab in Oxford, England, Malcolm was quite famous — already a giant in the burgeoning field of 2D nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) at which I was a mere practitioner. I learned a great deal from Malcolm, we collaborated on a few publications, but mostly we were avid squash partners every week for most of the five years.

I had played racquetball in California for three or four years, but New England had primarily squash courts. At the M.I.T. squash courts Malcolm helped me through the painful transition to the squash racquets with the small head somewhere on the end of a long shaft and squash balls as lively as lead. He won the first ten games without my earning a single point. Soon this changed and we became fiercely competitive. The squash racquet is also a deadly weapon, and one day Malcolm accidentally split my head open above one of my eyes, with blood gushing all over. At first he acted profusely apologetic and took off his T-shirt to help me stop the bleeding as we went straight to Mt. Auburn Hospital for stitches. Later he accused me of soiling his T-shirt. (You’d have to know his sense of humor.)

In the NMR spectrometer, the sample is placed in a high magnetic field surrounded by coils of wire that carry pulses of radio frequency tailored to excite certain nuclear magnetic dipoles. In the early days, it was difficult to excite the nuclei of the entire sample by the same amount because the coil shapes were not perfect — called pulse inhomogeneity. To correct this problem, Malcolm Levitt invented the composite pulse. Instead of a single 180 degree pulse, for example, he used a sandwich of 90-180-90 pulses in which the 180 pulse is phase shifted into a different axis. The middle 180 degree pulse thus reverses all the inhomogeneity accumulated at the halfway mark, thus refocusing the pulse. This simple and brilliant principle made possible by extension the first efficient decoupling schemes, i.e. continuous irradiation of one type of nucleus while observing another type, and the modern arsenal of prolonged triple resonance pulse sequences for protein structure determination authored by pioneering scientists such as Ad Bax and Lewis Kay.

Clearly Malcolm Levitt is well grounded in NMR theory and is a superb mathematician, which he vehemently denied to me. Soon after our first meeting we decided to spend an afternoon climbing Mt. Monadnock in New Hampshire. I asked Malcolm what he’s reading these days. “Quantum Chaos,” he answered. After I nearly split a gut laughing for a couple minutes, I realized he wasn’t joking. Not only was Malcolm current on all kinds of theory, he also knew the nuts and bolts of NMR very well, and schooled me on things like digital phase shifters, the way to get super accurate phase shifts, not available at that time on commercial NMR spectrometers.

Malcolm was depressed about breaking up with a girlfriend and I invited him to stay at our family summer home in Luck, WI. He is a talented player and composer of music, and brought his guitar along. We also managed a round of golf — not Malcolm’s specialty, but he was a good sport about it. He met my family, and I think the change of scenery for a week lifted his spirits.

The Levitt Family, 2006

I used to organize a ski trip every February for the Tufts Medical School Department of Biochemistry. We chartered a mini-bus for about 15 people and drove up to Loon Mountain Ski Area in New Hampshire. I invited Malcolm to join us. One of our Post-docs was a beautiful and charming woman from India named Latha. She had never skied before and had trouble getting up the beginner’s rope tow. I recall lifting Latha with one arm and with my other arm holding the rope carrying her uphill, with her giggling all the way. Malcolm and Latha bonded on that ski trip and began dating. Now they are married and have a lovely daughter Leela.

When my California cousin, Scott Ward, a “pyro” (fireworks expert), came to Boston with the Rolling Stones “Steel Wheels Tour” in 1989 and gave me three free front row tickets, Malcolm, Latha, and myself had a night of entertainment to remember.

There was a lot of interest in 2D NMR in those days and not many textbooks at an introductory level. Together with Bill Bachovchin and some financial help from Bruker Instruments, I persuaded Malcolm to give a series of lectures on the subject at Tufts and he agreed. These lectures grew into his masterpiece called “Spin Dynamics: Basics of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance,” published in 2001 by John Wiley. Lovingly illustrated by Malcolm, the book is a comprehensive treatise on the field of NMR as only Malcolm can explain things both in simple English, vector diagrams, and complete, uniform equations with all terms defined. It is a tour de force in the NMR field like no other book. A second edition came out in 2007. Malcolm was kind enough to give me (his “squash court enemy”) credit in the opening lines of the Preface for having started the process that led to his writing of this amazing book.

The last time I saw Malcolm was during a visit to Stockholm in April of 1998, where he was Professor of Physical Chemistry. There was snow on the ground and Leela was about 5 years old. We even managed to play a final grudge match on the squash court. Since that time, Malcolm has moved on as Professor in Physical Chemistry to the University of Southhampton, UK. In 2007 he was elected Fellow of the Royal Society. He has won dozens of prestigious honors, awards, and plenary lectureships. I am proud to be a friend of Professor Malcolm H. Levitt and his family, and will always remember our early days together in Boston.

- Tufts University School of Medicine (1985-2013)

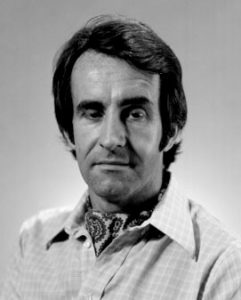

Prof. William B. Bachovchin

Prof. William B. Bachovchin. When you attack somebody in print, and they turn around and embrace you for being right, you’re dealing with an exceptional human being — like Bill Bachovchin. That’s essentially how Bill and I met in the early 1980’s. In a landmark paper, Cal Tech’s Roberts and Bachovchin had published in 1978 a pH titration of the 15N NMR signals in the active site of an isotopically enriched serine protease enzyme. When one of the two signals disappeared at high pH, Roberts and Bachovchin speculated on the presence of trace paramagnetic metals. Meanwhile I had published a set of equations showing that fast-exchange broadening of resonances undergoing such large protonation shifts, such as 113C and 15N, could be explained fully by proton exchange kinetics. Not being a big fan of the famous J.D. Roberts based on previous interactions, I was deliberately trying to zing them. But in a grant proposal that I happened to review and subsequent papers, Roberts and Bachovchin confirmed my theory, and it was the start of a mutual admiration society.

I knew that Bachovchin had gone from All-American football player in steel-milling Johnstown, Pennsylvania, to Wake Forest on a full football scholarship. When he majored in chemistry, the coaches were not happy. Soon he had to leave the football program because of a double hernia. Bill loved the seminal textbook on Organic Chemistry by J.D. Roberts and Marge Caserio, and went to Cal Tech as a grad student to work under the organic chemist and NMR specialist J.D. Roberts. He later did postdoctoral work at Cal Tech with John Richards, and still later with the biochemist, Bert Vallee at Harvard Medical School, where his interests took a strong turn towards biochemistry. Bill took a position as Assistant Professor of Biochemistry at Tufts Medical School in 1979, and was in charge of two NMR instruments by the time I joined him.

IN 1983 I resigned a tenured associate professorship at UCR out of disgust for academic politics. Then I had invested all my money starting a new business teaching golf via student video superimposed upon 3D biomechanical models I had developed and computer programs I had written with the help of a small SBIR grant. Underfunded, understaffed, and years ahead of my time, I lost everything, and with creditors calling, I needed a job. Bill needed someone to run his NMR facility, and after an interview trip to Boston, he offered me the job. Just for that alone, I will be forever grateful to him.

It took me some months to get back up to speed in the rapidly evolving world of multinuclear multidimensional NMR, but for the most part I was overqualified for the task. Initially I spent time designing and building improved receivers and pre-amplifiers for our existing spectrometers. Then I took part in writing grant proposals for obtaining several generations of new Bruker spectrometers. In my later years I became intimately involved with doing research and getting papers written up together with Bill and his students. Bill kept raising my salary so that I was eventually able to pay off my debts and earn enough 401K and Social Security funds to retire.

Over the 28 years I worked with Bill, our personal lives were intertwined with golf, ski trips, boating with his family at his cabin in New Hampshire, and we became close like brothers. Bill’s scientific genius has been an inspiration like nobody I’ve ever worked with or known, which is why, even though he is ten years younger than me, I list him as a mentor. He will read a paper in Science, Nature, Cell, or whatever journal, and underline a single sentence. Wading through all the irrelevant details and the chaff, he will find and remember the important take-home lesson in context. His mind is quick and restless. Perhaps that is how over the years he has been able to master areas of organic chemistry, NMR spectroscopy, boron chemistry, enzymology, genetics, immunology, drug design, oncology, patent law, corporate law and finance, and the pharmaceutical business. This has enabled him to start three new companies, the first of which I co-founded by recruiting the first $6 million investment from one of my golf connections. Bill is also currently in great demand as an expert witness testifying in pharmaceutical lawsuits.

As a person, Bill is harder working, more driven, more honest, more generous, and more loyal to his friends, students, colleagues, and family than anyone I’ve ever met. His son, Dan, has inherited his father’s intellect and expertise, picked up his mantle, and is blazing a fast trail as a young, well-funded Professor with a sizeable research group at Sloan Kettering in NYC.

Together, Bill and I have written important papers such as the imidazole ring-flip theory of serine protease catalysis. It is too beautiful not to be true, and I am hopeful that before long the evidence will come along to confirm it. Bill has made important discoveries in the world of diabetes, such as his patent on Merck’s Januvia which has earned billions of dollars for Merck and many millions in royalties for Bill’s companies. His inherently trusting nature has been tempered by experience in how to choose synergistic and competent business partners. With the right partners and financial backing, Bill’s continuing blitz of discoveries on smart cancer drugs will certainly result in exciting new blockbuster drugs. It has been one of the joys of my life to know and collaborate scientifically and personally with Prof. William W. Bachovchin.

Jim Sudmeier

Luck, WI

May 2, 2020